Winnebago County regains jobs lost in pandemic, skills shortage threatens recovery

September 30, 2020

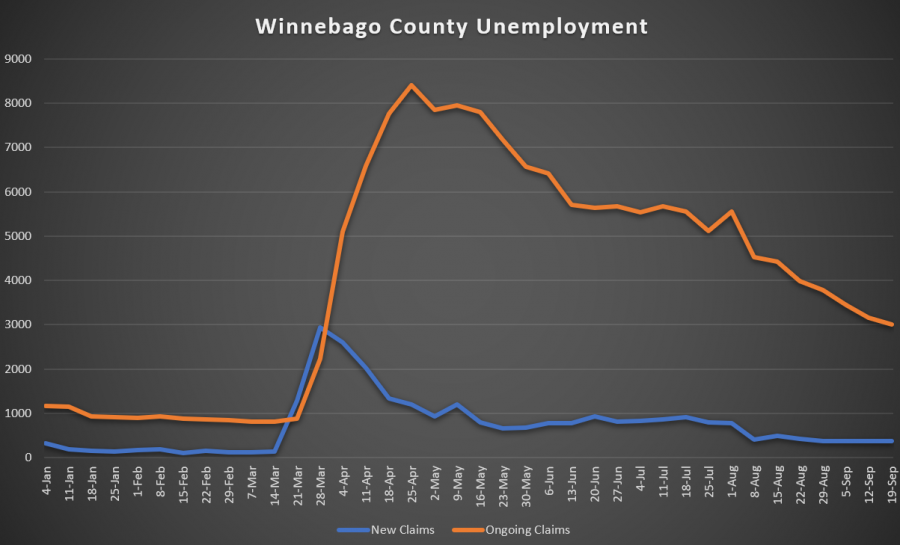

After exceeding Great Recession levels back in April, the unemployment rate in Winnebago County has normalized, even as issues that plagued the economy before the pandemic have been amplified in its wake.

The unemployment rate gradually declined throughout the summer as businesses continued reopening, according to preliminary statistics from the state Department of Workforce Development.

The August unemployment rate in Winnebago County was 5.1% with roughly 4,620 people collecting benefits, meaning 7,280 jobs have been added since April when unemployment was 13.2%, the DWD reports.

Even so, industries such as leisure/hospitality, government, education/health services and other services have not fully regained jobs lost during the statewide Safer at Home Order, according to DWD Economist Ryan Long.

“Leisure/Hospitality — as of August — is still down 3,300 jobs from March,” Long said. “But the biggest loser is actually government, particularly at the state and local levels. Paradoxically, health care is also down 1,700. Retail is actually up 1,500.”

While the economy has proven resilient as unemployment has gone down, Fox Valley Workforce Development Board (FVWDB) CEO Anthony Snyder said employers are struggling to find highly skilled workers, a problem they faced before the pandemic.

“If you’re a large manufacturer, you are still seeking skilled labor now, just like you were in March,” Snyder said. “Nothing has changed.”

That’s because a new wave of automation — known as Industry 4.0 — is emerging, and replacing high-wage, low-skill factory jobs with high-skill, high-wage jobs. Prior to the pandemic, there were 1,500 local tech jobs that companies couldn’t fill.

A 2019 survey of 104 manufacturers in Northeast Wisconsin found that the most in-demand jobs over the next two to three years include process engineers, data management analysts, cybersecurity officers, industrial computer programmers, data engineers, data architects and application developers.

The pandemic has forced manufacturers to continue to explore Industry 4.0, according to Ann Franz, director of the Northeast Wisconsin Manufacturing Alliance, the organization that conducted the Industry 4.0 survey.

“The Alliance’s Industry 4.0 task force is growing from a year ago, [from] 20 people to now 70,” Franz said. “Technology and having a skilled workforce is critical to this region.”

As low-skill factory jobs have become less abundant, a larger chunk of people have transitioned into low-skill, low-wage service jobs, Snyder says.

“We now call them ‘essential workers’ in many cases,” he said. “The delivery driver bringing your food to you is an essential worker. The worker stocking shelves at the grocery store is an essential worker. A lot of the time, these essential workers are the lowest-paid people out there.”

To improve the quality of life for many of those workers, Snyder believes the United States needs to reinvest in workforce development to “upskill” its labor force for the jobs of tomorrow.

However, he said workforce development boards such as FVWDB are significantly underfunded to provide retraining programs because the federal government had slashed workforce development funding.

In a perfect world, Snyder says Congress would have signed another stimulus package into law this summer to fund retraining programs.

In July, Congress failed to pass another round of stimulus. Subsequent efforts have fallen through as talks between Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill have stalled.

If a deal can be reached, Snyder hopes Congress can increase funding for retraining programs to help unskilled workers find a career that will allow them to feed their families and meet the needs of a 21st-century economy.

“Some people never fully launched a career; they got a job after high school and they never were able to advance because of a lack of skills or a lack of education,” Snyder said. “Ideally, what I would like to do is take the underemployed cashier or the now unemployed bartender and get them into a retraining program that we will pay for.”

Beyond covering the cost of a program, Snyder would like to cover living expenses such as rent and utilities to allow participants to focus on their education.

However, FVWDB’s funding has shrunk to the point where Snyder either has to “serve fewer people” or “serve as many people as possible with fewer dollars,” meaning the workforce board cannot afford to pay for retraining programs without more help.

Ultimately, increasing the pool of skilled workers during the pandemic will put the economy in a position to thrive in a post-pandemic society, Snyder said.