A family never forgets

November 21, 2019

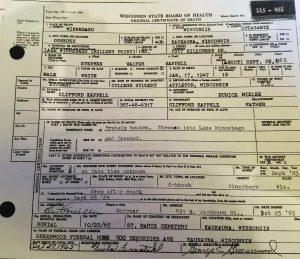

This series includes interviews with the late Stephen Kappell’s best friend, sisters and the Oshkosh Police Department. The case files and evidence were unable to be located or were destroyed by authorities. Numerous news articles as well as autopsy and crime lab reports were examined to gather information.

On an afternoon more than 56 years ago, the body of an 18-year-old UW Oshkosh college freshman was found floating in Lake Winnebago at Menominee Park.

The man was found nude and beaten, with his hands and knees bound, and a 30-pound rock attached to his feet. A coroner’s inquest could not determine whether the man had died by suicide or homicide.

Over half a century later, the victim’s family still hasn’t received any answers to who or what caused the violent death of Stephen Kappell.

‘56 years later, I still cry’

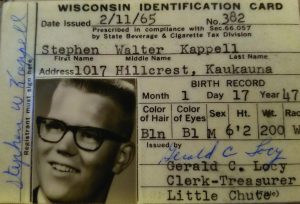

Martha Kemp was only 8 years old when her brother Stephen disappeared, but she’ll never forget the last time he returned home from college for a visit with his parents, Clifford and Eunice, and three younger siblings Martha, Robert, 10, and Mary Jo, 11.

“He picked all three of us up and stood up and gave us the biggest hug ever,” she said. “He was truly happy and we were happy to see him.”

That happiness was strained on Sept. 28, 1965, when Stephen disappeared from his dorm room, at what was then known as the Wisconsin State University at Oshkosh, where he’d been a freshman for only two weeks.

“In our hearts, we knew something wasn’t right,” Kemp said.

On Oct. 18, 1965, the police knocked on the door of the Kappell home in Kaukauna and notified the family a body had been found in Lake Winnebago and it was likely Stephen’s.

“Mom and Dad sat us down in the living room and then they explained that they found Stephen and that he was found in the water … and that he was dead,” Kemp said. “I just remember asking my dad, ‘Aren’t we going to go after the people who did this? Aren’t we going to find the people who did this to him?’”

“That will never bring Stephen back,” her father told her.

As the firstborn, Stephen shared a close relationship with his mother.

“To learn that your son had to go through a brutal beating, I’m a mother and I can’t imagine what she went through,” Kemp said.

According to The Post-Crescent of Appleton, Wisconsin, Stephen’s parents viewed his body before it was transferred to Milwaukee for the autopsy, but were unable to make a positive identification due to decomposition.

Stephen was laid to rest on Oct. 22, 1965.

That Christmas, Clifford brought a puppy home.

“It was a brown poodle and Mom was upset with that,” Kemp said. “She said, ‘You can’t replace a son with a dog,’ and he said, ‘I never want to replace my son, but we need to have something to bring some happiness.’”

Kemp recalls her mother sitting in a rocking chair that Christmas Day in 1965, grieving the loss of her son just two months earlier, and repeating, “The dogs gotta go, the dog’s gotta go.”

“And that little puppy jumped up on her lap and that was her buddy ever since,” Kemp said. “Dogs know who they need to comfort and help.”

They named the puppy Coco and he stayed.

Kemp said her mother never stopped grieving for Stephen, even on the day she died.

“I went in that morning and I said, ‘Good morning, Mom, I’m here,’” Kemp said. “She said to me, ‘But where’s Stephen?’And that was the last thing she ever said to me.”

For the Kappell family, nothing was the same after Stephen’s death.

“Everything changed,” Kemp said. “Nobody talked about anything like that. I didn’t want sympathy from my classmates. I just remember not liking them saying, ‘I’m sorry about your brother.’ You don’t know how it affects a family. Sometimes my mom would cry out his name at night. 56 years later, I still cry.”

The investigation

It was raining on the night Stephen disappeared. Stephen’s best friend, Timothy St. Aubin, asserts a paper boy reported seeing some men with Stephen that night.

“They saw some fellas with this guy and I don’t think he was being handled too nicely,” St. Aubin said, alleging the police didn’t follow up on that lead.

The Post-Crescent reported:

The Saturday Stephen’s body was discovered, divers searched the lake for clues. The following Monday, police and sheriff’s department officials searched the shoreline near the breakwater in Miller’s Bay.

Three days later, police made a house-to-house survey of the area and began questioning students in Breese Hall. WSU-O campus officials said they were “cooperating extensively” with authorities.

That same day, Stephen’s body was identified using dental records and fingerprints.

A week after his body was discovered, Civil Defense personnel, boy scouts and law enforcement officials searched several acres of shoreline. Boats were used to drag the lake.

Documents indicate two vitamin C tablets from WSU-O were submitted into evidence along with an athletic belt found near the boat launch and a different athletic belt used to attach the rock to Stephen.

“That [belt] was around his waist with a tethered line to that weight,” St. Aubin said. “That’s not something you wore to hold up your britches.”

The day after Stephen’s body was identified, Oshkosh Police Chief Harry Guenther said he was no longer discounting the possibility of suicide. He said witnesses were reluctant to come forward with information for fear of having their names published in the newspaper.

Newspapers reported an unidentified student was the last one to see Stephen alive. The student said Stephen told him he was leaving campus and when the student tried to talk him out of it Stephen “just walked away.”

In the book “Staggered Paths: Strange Deaths in the Badger State,” a 1965 WSU-O football teammate was interviewed in 2016 and said he heard “through the rumor mill” that Stephen’s girlfriend broke up with him and Stephen “jumped from a boat with a rock tied to him.”

But St. Aubin suspects foul play.

“Either he got in a mess with some townies or someone else had a reason to do him in,” St. Aubin said. “You don’t take all your clothes off, beat yourself up, and go out in the lake so far that when you drop the rock you’re underwater.”

Suicide or homicide?

Police Chief Harry Guenther sent a letter to District Attorney Gerald Engeldinger two weeks after Stephen’s body was identified, requesting a coroner’s inquest.

The Post-Crescent reported county Coroner Art Miller believed scheduling a coroner’s inquest was premature.

“I can’t see this case as anything else but murder based on the information turned up,” Miller said. “If there is any information to the contrary it was not supplied when the investigation was underway.”

St. Aubin said the inquest was rushed.

“From the day he disappeared to the inquest, it was all done in three or four months,” St. Aubin said. “They had the inquest when I was still a freshman.”

“Was Stephen Kappell the likable, polite, husky athlete and ardent fisherman, murdered?” a Northwestern article questioned. “Or was Stephen Kappell the insecure, emerging-from-adolescence young man, plagued with self-doubt, driven to self destruction?”

If Kappell committed suicide by drowning, his death would have been excruciating.

“He was a lifeguard. He taught us how to swim. Water was something to be respected,” Kemp said. “I just don’t feel that he would take his life with water. He had too much love for swimming and fishing, and I just don’t think that would be his escape.”

St. Aubin said the city of Oshkosh tried to shut the case down quickly.

“First of all, do a thorough investigation and not wrap it up so quick to say he committed suicide,” he said. “Something smells.”

Coroner’s inquest

Six jurors would determine Stephen’s cause of death at the coroner’s inquest, which took place less than two months after the discovery of his body.

The inquest lasted 10 hours and included testimony from 22 witnesses including classmates at Kaukauna High School and WSU-O, police and crime lab officials, Stephen’s former girlfriends and his parents, according to The Northwestern.

The Post-Crescent reported:

Coroner Helen Young testified Stephen was unconscious when he entered the water. Young qualified her statement by saying Stephen “could have been conscious when he entered the water and then rendered unconscious by striking something in the water.”

Young reported finding evidence of a medication in Stephen’s system, something similar to a time-delay cold capsule, which she speculated could have caused unconsciousness. She said she couldn’t determine if he received a concussion from his head injury, but it also could have knocked him unconscious.

An official testified the bindings used on Stephen’s body fit together to form the left leg and rear section of a pair of khaki trousers. Traces of similar men’s trousers were found at the boat launch about 500 yards southwest of where Stephen’s body was found; however, documents indicate this type of pants were very common at the time.

The official said it was not determined if the trouser remains belonged to Stephen. His mother testified his waist was size 36. Officials testified the belt used to attach the rock was a size 38 and traced back to Stephen’s football uniform.

According to media reports, officials portrayed Stephen as a “disturbed man with suicidal tendencies” during the inquest.

Officials key in on knots

One key piece of evidence discussed at the hearing were the knots used to bind Stephen. The knots were granny style, which is considered inferior to a square knot. An official testified the difference between granny knots and square knots is square knots have no holding potential.

Stephen’s mother testified Stephen was a fly-tier and knew how to tie a square knot. According to the Northwestern, Stephen teased his mother because she could not tie a square knot.

Kemp recalls her mother saying investigators focused on details leading the jury to believe Stephen committed suicide.

“They just dissected every little thing they found to side it one way or the other and it always seemed like they were looking for a deeper meaning,” she said. “They really pushed it to be a suicide.”

The Post-Crescent reported Clifford Kappell testified he took Stephen to see a doctor after his son had a run-in with the law five months earlier. The doctor determined nothing was wrong with Stephen. Clifford also testified Stephen had spent the summer working at a paper mill and had done so well they wanted him back the following summer.

When St. Aubin was called to the stand, he sat next to the judge.

“Whoever was representing the city of Oshkosh kept wanting me to say it was a suicide,” St. Aubin said. “I said, ‘No it wasn’t.’ I just don’t like the way this whole thing has happened.”

Engeldinger arranged for three psychiatrists trained in criminology to be present during the inquest to evaluate the testimony. All three testified they felt Stephen committed suicide based on motive and intent.

“There is a possibility, or even a good probability, death was caused by self-destruction,” The Northwestern reported one psychiatrist testifying.

The Post-Crescent reported another psychiatrist testified a person “as disturbed as this boy” could have wanted his last play to be “a grandstand play to fulfill his feeling of inadequacy.”

“Under oath, I am convinced Steve was murdered,” Clifford testified at the hearing.

The coroner’s jury deliberated for 20 minutes before returning with a verdict written on a napkin which said, “We the jury feel that there is not enough concrete evidence to prove when, where or how the victim entered the water to prove either suicide or murder and it is the jury’s recommendation the case remain open for further investigation.”

Coming next week: The Kappell family reaches out to the Oshkosh Police Department for answers, but the police have no open cases.