‘Algoma Boulevard riots’ rocked Oshkosh 50 years ago

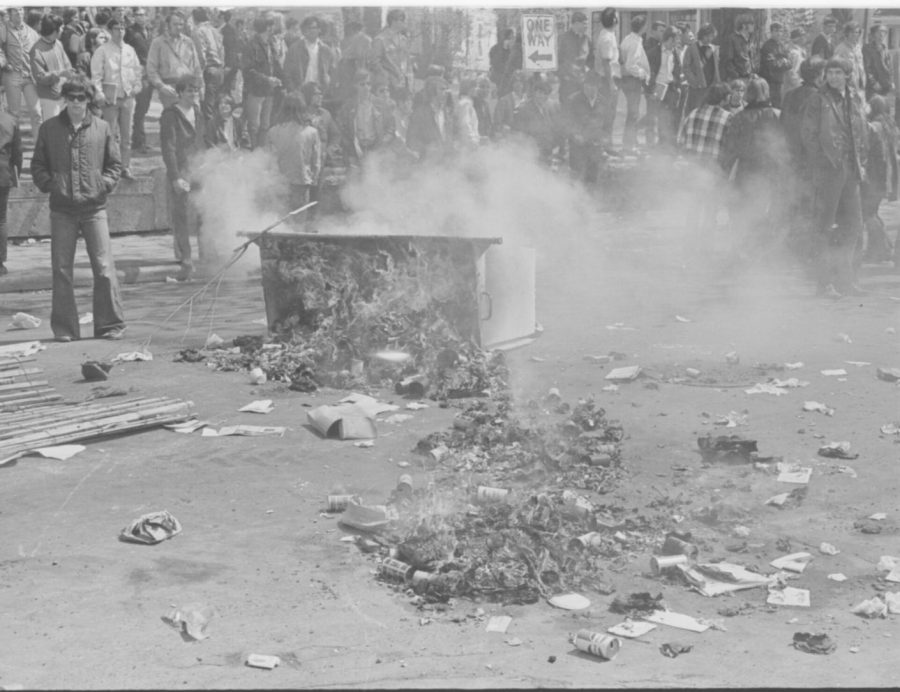

UW Oshkosh Archives Photo — In 1970, students on what is now UW Oshkosh lit tires and trash cans on fire to protest the war and Algoma Boulevard safety concerns.

April 30, 2020

Fifty years ago, a growing anti-war movement erupted on what is now the UW Oshkosh campus when thousands of students rioted, blockading Algoma Boulevard, lighting tires and trash cans on fire and digging up a 30-foot section of road with pickaxes and shovels.

The incident became known as “the Algoma Boulevard Riots,” a cultural collision between President Richard Nixon’s “moral majority” and the counterculture in Oshkosh, according to research from UWO history professor Stephen Kercher and students Jean Westerhaus and Alex Schoenbeck.

An emerging counterculture

The 1960s had been a decade of growth on the Wisconsin State University at Oshkosh (WSU-O) campus; each year the campus saw roughly 1,000 more students than it had the year prior. The campus’ continued growth became a point of contention among city residents, according to UWO Archivist Joshua Ranger.

When the city voted in 1869 to create the campus, the intention was to create a small teachers college with a few hundred students, but the baby boom after World War II resulted in a campus of well over 10,000 students. And by the height of America’s counterculture revolution, students began living off campus in the same neighborhoods as many of the city’s residents.

“You’ve got men with long hair, hippies and girls who’re not shaving or not wearing bras, living next to families; it was scandalous to all these different types of people at the time,” Ranger said. “It was like the things they saw on the evening news were now in their own town.”

By the late 60s, Kercher said the anti-war movement had taken hold in campuses across the United States, and WSU-O was no exception, as the campus had a dedicated group of student activists. For the young men on campus, the threat of getting drafted was always looming.

In October 1969, student organizers asked the university to cancel classes for a teach-in to educate the community about the horrors of the Vietnam War, the same day as the nationwide Moratorium to End the War.

When the university president refused to cancel classes on Oct. 15, students organized a panel discussion in Fletcher Hall and a two-hour assembly criticizing the war on the lawn in front of Dempsey Hall. The day was capped with a 2,000 person candlelight march to the Winnebago County Courthouse.

Kercher said the university allowed those demonstrations because it did not want to deal with the potentially negative consequences of a larger event, such as “Black Thursday” in November of the previous year, in which 94 African American students were arrested for protesting.

A divided community

Black Thursday and the Oct. 15 anti-war demonstrations didn’t go unnoticed by the larger Oshkosh community, which, in the late 1960s, was deeply divided on issues like the war in Vietnam, civil rights and feminism.

“Oshkosh, like so many cities throughout the United States, was really divided on these critical issues that really had Americans fighting against each other,” Kercher said. “We have lived in very partisan times over the last several years, but it’s always a good reminder for us to realize that there have been moments like this in the past when American society was deeply divided.”

Those divisions, Ranger said, caused some residents to begin wondering “why are we, the taxpayers, supporting these kids who don’t know how good they have it?” At that time, tuition was completely subsidized by taxpayers.

The draft lottery in December of 1969 and Nixon’s April 1970 announcement that he was sending U.S. troops into Cambodia further frustrated WSU-O’s students.

‘The traffic problem’

Algoma Boulevard, a street that goes through the heart of campus, was — and still is — busy. When classes are in session, crowds of students will emerge at intersections, waiting for traffic to clear. But in the 1970s, Ranger said the situation was much more dangerous than it is today.

“Nowhere else in Oshkosh would you have to wait for hundreds of people to cross the road; it’s kind of unusual,” he said. “People were driving too fast, and there was the perception that [drivers] were trying to even hit students, or get really close to it to scare them as some sort of outlet for their frustration over what was happening to their city.”

On May 1, 1970, conservatives in Oshkosh had crafted an event dubbed “Law Day, USA.” The plan was to have the day serve as a testament to Nixonian ideas of law and order, promoted by local public figures and school children.

However, WSU-O students used the day to raise awareness about the Algoma Boulevard situation. Students handed out pamphlets with information about “the traffic problem,” and eventually roughly 400 assembled and closed Algoma to local traffic, building barricades with logs, concrete bumpers and large garbage containers.

The incident, Kercher says, only inflamed the growing animosity between the students and city residents, who believed in Nixon’s idea that “America needed law and order to put an end to the demonstrations and the chaos that was being stirred up by spoiled rebel rousing, drug addicted, sandal-wearing hipsters.”

Animosity boils over

A few days later, on May 4, 1970, four Kent State University students were killed and nine were injured protesting the war in Vietnam. That night, 250 WSU-O students attended the Oshkosh Common Council meeting to ask the city to address the Algoma Boulevard issue.

The council provided the students with no guarantees that they would address the issue, which enraged them. One student was reportedly so upset that he told the council: “You’ve lied to us, you’ve beat around the bush. Well, damn it, it’s too late. I’m going out into the streets and so is everybody else here.”

At 11 p.m. that day, roughly 2,500 students poured onto Algoma Boulevard. They set up barricades, started tires and trash cans on fire, and even began digging up a 30-foot section of the road with pickaxes and shovels.

“What started as a public safety issue really sort of morphed into a way for students to really vent their rage at the continuing conflict between law and order authority — the Nixon administration — and young people,” Kercher said.

The Nixon administration’s extension of the Vietnam War, the draft lottery of 1969, the Kent state tragedy and the city’s non-commitment to the traffic issue had made students feel that their personal safety was being endangered by a generation of adults who didn’t respect them.

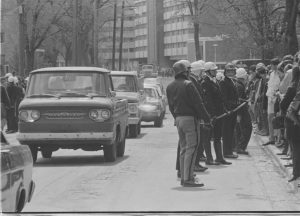

Those feelings of fear, anger, disappointment, dread and animosity had finally boiled over on Algoma Boulevard. The Winnebago County police and officers from 15 other police agencies — all wearing riot gear — intervened and dispersed students.

The next morning, hundreds of police officers kept students at bay while plows and equipment from the Winnebago County Highway Department moved down Algoma Boulevard to reopen the road.

Some enraged students threw rocks and chunks of concrete at officers. The police made arrests for unlawful assembly and disorderly conduct. As students were being arrested, others yelled reminders about the Kent State killings.

One student reportedly yelled: “This is it….That’s why we’re here…the war. It was the road until yesterday. Now it’s what happened at Kent State.”

The next day, 15 mph speed limit signs were installed. The same day, the student body president reportedly said Algoma Boulevard was “a dead issue,” and that “Cambodia” and “not the street” were the cause of the protests.

The Silent March

The student protesters had a strike planned for May 7. But, at a memorial service that afternoon for the Kent State students killed on May 4, WSU-O President Roger Guiles, who had expelled the 94 students for demonstrating on Black Thursday, lowered the campus flag in honor of the dead students.

In response to Guiles’ gesture, student activists toned down their planned march to the downtown Selective Service office. WSU-O student Harley Christensen reportedly said: “What can we accomplish by violence? Nothing. What can we accomplish by peace and love? Everything.”

Kercher said the student activists had recognized that more destructive action was a dead end, and decided to take a more peaceful course.

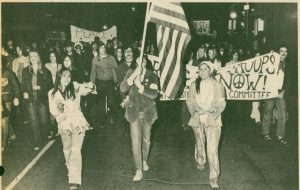

That night, 4,000 people, including WSU-O students, local high school students and Oshkosh residents, marched down Main Street. Four students carrying crosses with the names of the dead Kent State students led the silent march, which occurred peacefully.

That summer, on Aug. 24, 1970, four radical anti-war protesters bombed Sterling Hall on the UW-Madison campus, killing one young researcher and injuring three others, sending a chill through the anti-war movement across the country.

Throughout the anti-war movement, protesters were forced to grapple with the results of radical tactics. In the Sterling Hall bombing, the radicals had finally gone too far, forcing activists to wonder if extreme measures were the best way to convince law-abiding Americans to see their point of view. In Oshkosh, peaceful protest inevitably beat out violent riots, and the riots on Algoma Boulevard faded into history.

“The death of that young man on the UW-Madison campus sent a chill throughout the anti-war movement in Wisconsin more than in other states throughout the country,” Kercher said. “Madison’s not that far away [from Oshkosh] and there were a lot of people who had connections to Madison and the fallout from that bombing reverberated throughout the Oshkosh campus.”

Editor’s Note: If you remember the Algoma Boulevard Riots and would like to share your story, email UWO Archivist Joshua Ranger at .