Taking a stand against racial discrimination

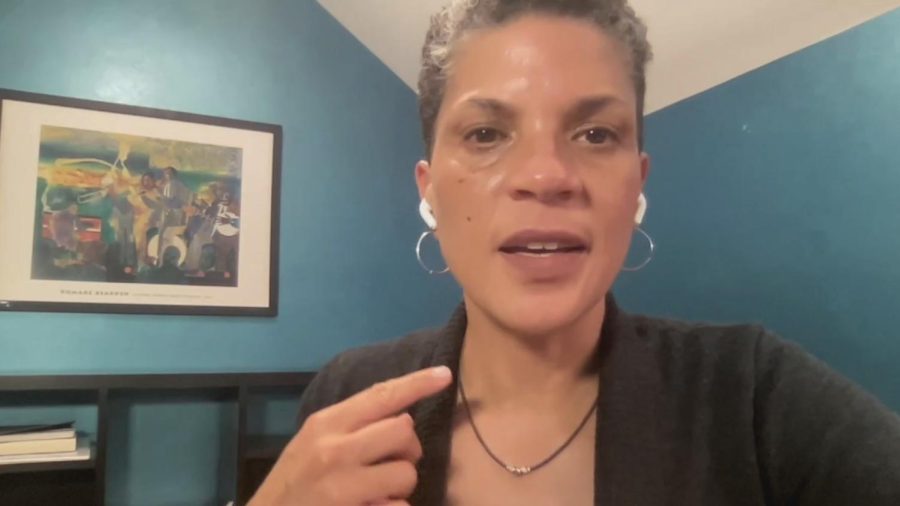

Michelle Alexander, civil rights lawyer, legal scholar and author, discusses police brutality, modern racism and mass incarceration of minorities.

April 19, 2022

Discrimination takes all different shapes and forms. In one way or another, it affects all of us. But some people and communities have a rougher road to traverse. Luckily, there are a myriad of different people and communities fighting on their behalf, and Michelle Alexander is one of them.

Alexander is a civil rights activist and author of “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.” The best-selling book discusses modern forms of racism and mass incarceration, comparing the treatment of minorities in modern America to that of African Americans during Jim Crow segregation. Alexander presented her years of research and experience during a virtual event last week, hoping to illuminate issues that she believes are widely ignored by the general public.

In the 1990s, she began working with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a nonprofit organization fighting for equal rights. When she started with the ACLU, Alexander primarily fought against the state of California, which was working to eliminate the use of affirmative action in college admissions.

“I came aboard ready to join teams of lawyers aiming to defend affirmative action,” Alexander said.

She realized that her offices were being flooded with complaints about police brutality and misconduct.

“A friend of mine mentioned that he had been going to community meetings to talk about affirmative action, and he kept being interrupted by people asking what they could do to stop the police who were hounding their families. So I began to become increasingly interested in representing victims of racial profiling and police misconduct, an area receiving little attention at the time.”

Alexander’s growing interest in police brutality cases led her to create a new initiative. Her team sued the California Highway Patrol for racial profiling, but they were seeking to sue other agencies as well. She said she created a hotline for the victims of police injustice.

“A few minutes after announcing the hotline number on the evening news, we received thousands of calls; our system crashed,” she said.

Looking to find a plaintiff that could solidify their lawsuit against the Oakland Police Department, Alexander conducted in-person interviews of victimized young men who had called the hotline. She elaborated on a particular young man who she had talked with.

“There was this young, 19-year-old man who walked into my office with a books-worth of papers. He had taken detailed notes of his encounters with the police over the past year—the notes mentioned every time he’d been stopped, every time he was searched or frisked, and what arrests were made. In some cases, he had badge numbers and the names of officers.”

Alexander said she started to get excited.

“‘He’s the one,’ I thought to myself. ‘He’s our dream plaintiff.’ But I started asking him more questions and found out that he was a felon.”

Alexander’s team was screening interviewees for felonies, assuming that a criminal record would jeopardize their court case.

“We knew if we [represented a felon], law enforcement would be all over us. We couldn’t put someone with a felony record on the stand in front of a jury and expose them to cross-examination about their criminal past. That would just deflect the jury’s attention away from the police misconduct.”

She confronted the young man about his felony charge, and he responded, “Yea…I got a felony. But the police planted drugs on me, and they framed me and my friend.”

“No, no. I’m so sorry,” Alexander said, “But I can’t represent you.”

She tried reasoning with the young man, but he was persistent, saying that he only took the plea deal to avoid jail time.

“‘What’s to become of me?’ the young man said. ‘Do you know that I can’t get a job anywhere because of my felony record? What am I supposed to do? I can’t even get food stamps.’ He grabbed his notes and ripped them up into pieces, throwing them in the air. He then looked at me and said, ‘I can’t believe I trusted you. You’re no better than the police.’ And he took off.”

Alexander said she had an epiphany a few months later while reading about a police scandal in the paper.

“It turns out that the police’s drug task force had been planting drugs on suspects and beating folks up in this young man’s neighborhood,” she said.

One of the officers charged in the scandal was the officer the young man identified as having planted drugs on him. Realizing this, Alexander said she thought about what the man said.

“I thought to myself, ‘The young man was right about me; I was no better than the police.’ The minute he told me he was a felon, I stopped listening.”

This was the beginning of her thinking deeply about her role as a civil rights lawyer. She tried contacting the young man but was unable to reach him.

Alexander encouraged everyone to be proactive and to organize in fighting for change.

“As the civil rights movement was growing, if you wanted to join the movement, you knew where to go, [but] today, that’s not the case,” she said.

She outlined the necessity of forming grass-root initiatives to raise awareness for racial injustice, a sentiment echoed by Damira Grady, Associate Vice Chancellor for Inclusive Excellence and University Diversity Officer at UWO.

“I like the proactive approach,” Grady said. “I understand the pain when we have the reactive movements around things,” she said, referencing the recent BLM protests and other activist rallies throughout the country. “I wonder what it’s going to take to end mass incarceration.”

Alexander outlined her thoughts on possible solutions to the mass incarceration problem, which she said disproportionately targets minorities.

“There’s no one piece of legislation that could end mass incarceration overnight. But one thing that we can do is to tell the truth. I don’t just mean telling the truth about how awful [racism and police brutality] are. I’m talking about the kind of truth telling that poses some meaningful challenge to the status quo. That requires organization, courage and refusing to cooperate with the prevailing institutions and ideas around what justice is and what justice looks like.”

Grady explained that some people tend to stop listening when they hear information they disagree with. Alexander acknowledged this.

“People who don’t want to listen aren’t going to listen. But I don’t think it helps to attack people for their ignorance,” she said. “So, when people claim that there’s not really racism in the criminal justice system, they may have good reasons for believing that. But being able to acknowledge our own blind spots can help open the door to raising awareness.”