Gerrymandering: Democracy’s greatest adviser or adversary?

July 14, 2020

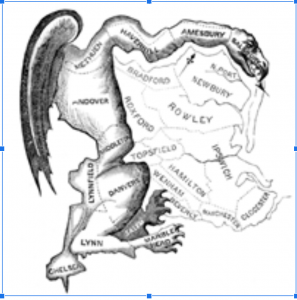

In a democracy, it is the voters who choose the politicians to represent them in Congress. However, what if the politicians began cherry picking voters to increase their chances of winning? It’s been happening for centuries, and it’s called “gerrymandering.”

Gerrymandering is a term used when voters in congressional districts are divided or combined to favor one political party over another. While gerrymandering isn’t new, recent advances in data gathering and analysis makes it easier to accomplish as well as address.

How is it done?

Political districts are man-made boundaries, usually drawn by state legislatures after a national census once every 10 years. If one party has a majority in the state legislature they can draw districts that favor their party.

To do this, mapmakers often must draw odd shapes to include or exclude the voters they want.

This happens in one of two ways: “packing” or “cracking.”

Packing is when a district is packed with voters of one party. This concentrates the other party’s voters into fewer districts. As a result, their party wins fewer districts overall.

Cracking is when an area with a high amount of Democrats or Republicans is broken up into multiple districts. Voters are broken up to reduce their power in a given district.

How do they know?

So, how do legislatures know who you voted for or what party you belong to when drawing new district lines in modern times?

Data, and lots of it. It is often collected by third party entities willing to sell it off to politicians who are looking to gain an edge on the political landscape.

This data can come from election results of each precinct, surveys of voters in exit polls, public data (census data and property records) and the data people create and share every day from smartphones, fitness trackers and other gadgets.

All of this data can be used to create algorithms that categorize who is more likely to be a democrat or republican based on your demographics (age, gender, education), where you live and your behavior online and in the store.

Algorithms are essentially instructions that tell a computer what to do with all of the data and inputs it receives. They are designed to process and analyze massive amounts of user data and can make suggestions, inferences and predictions.

How does this apply to politics?

Big data made national headlines during the 2016 presidential election. According to Facebook, a third-party data analyst company, Cambridge Analytica, gained unauthorized access to 87 million Facebook accounts leading up to the election.

Cambridge Analytica then used this user data to create algorithms to target different types of voters with different types of ads.

Peer-reviewed research on big data and politics was published in the American Journal of Political Science using tweets on Twitter by Northeastern associate professor Nick Beauchamp.

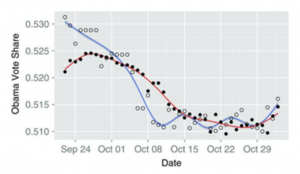

Beauchamp’s goal was to test whether political tweets could “be used to predict polling variation and changes” in the nine weeks leading up to the 2012 presidential election.

To test this, he used over 100 million political tweets and 1,200 state-level polls as a benchmark. State-level polls are more accurate than national polls.

Beauchamp’s analysis found that the tweet data closely mirrored state level polling and could be used to “track and to some degree predict opinion polls.” He even found certain words and behaviors were more strongly correlated with different political leanings.

For example, where left-leaning areas had more political tweets on external sources (URLs) and regional issues, right-leaning areas had higher political retweets and activity on national issues.

How does this apply to gerrymandering?

From someone’s age and address to what someone searches online or posts on social media, everything can be tracked and recorded into algorithms that will determine the likelihood and strength of political leaning.

This can be used to tailor advertisements that speak to one’s political profile (like Cambridge Analytica), predict and respond to political opinion changes (like with Twitter) and can be mapped, “cracked” or “packed” by politicians who choose what voters they want in their district.

While data technology means gerrymandering is more sophisticated than in 1812, data can also be used to identify inconsistencies, alternatives and inform constituents.

For example, what if, instead of politicians in state legislatures, a computer program redraws the districts to minimize the distance between each person and the center of their district, removing all other factors while keeping population even?

A graduate student at Oxford University, Jory Flemings, conducted such an analysis using an algorithm. His model drew districts that were a third more compact than the districts drawn in the 115th congress.

These computer-generated districts increased swing districts from 15% to 28% indicating elections would be more competitive if population and compactness were the only factors.

A range of computer models can be created to model alternative districting plans and to flag possible partisan gerrymandering that is so severe that it unfairly represents voters.

However, the definition of fairness is not universal and can be measured in many different ways. Any computer model raises its own questions about how fairness is measured and who it is for, according to Moon Duchin, associate professor of mathematics at Tufts University in Massachusetts.

Provisions to help guide a fair democratic process do exist in legislation like the 1964 Civil Rights Acts, which bars any state from drawing political boundaries that interfered with the representation of minorities.

But beyond race, gerrymandering is largely unrestricted. In 2019, the US Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that federal courts could not determine if a district is too politically partisan and that such a decision needed to be made in Congress.

This begs the question, to ensure a stronger and more representative democracy, do we leave the power of redistricting in the hands of man or turn it over to the hands of a machine?

I think there are two factors that need to be brought to light. First, we live in a society that is more mobile and connected than ever before.

Ultimately, populations are ever changing and increasingly on the move, but tracking political trends through technology is becoming easier and easier. Thus, gerrymandering will likely become more convenient and valuable.

But, this leads to my second point, if we put all of our political trust outside of humanity and hand it over to a computer, what does this say about the confidence within ourselves to make the right decisions about our democratic process?

Recently, a few states have found another option that can consider both sides while being nonpartisan. Nearby Michigan, specifically, voted to create an independent redistricting commission to oversee the drawing of congressional districts that comprises four Republicans, four Democrats, and five individuals who do not identify with either party.

While certainly not the end-all, it shows yet another option.

Democracy should be guided by data technology because technology is not going away. While the amount of information today is unparalleled, data has long played a role in shaping society, for better or worse.

Data and technology are just tools, and like all tools, can be used to rebuild and reinvent or tear down and divide. How we harness the power of data is a test to our character and the soul of our nation in which we belong. We should use technology to aid us, not restrict us or replace us.

Sadie Baile contributed to this article.