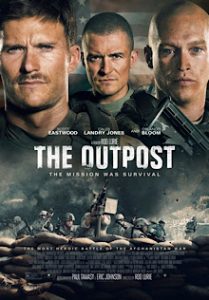

‘The Outpost:’ a modern war film with meaning

October 7, 2020

“The Outpost” is a modern war film directed by Rod Lurie with a script from the writers who brought us “Patriots Day,” “The Finest Hours,” “Fighter” and a slew of “Air Bud” movies. So quite the odd filmography.

A small unit of U.S. soldiers is alone at the remote Combat Outpost Keating, located deep in Afghanistan, battling an overwhelming force of Taliban fighters in a coordinated attack.

The goal: survive.

This is a true story from 2009 that became known as “the bloodiest American battle of the Afghanistan War,” and this group of American soldiers became the most decorated men of that time.

This film was released in early July, but I was reluctant to watch it because I have a huge problem with war films set in the modern-day. When a studio sets out to make a modern war film nowadays, they usually reach out to the military to get access to military-grade equipment like tanks, jeeps and other weaponry.

However, the military does not graciously do so without strings attached. They must first approve the script, meaning that the majority of the time, war films set in the modern-day are essentially propaganda to recruit Americans to the military by making war look “badass.”

Films like “12 Strong,” the “Transformers” films, the works of Roland Emmerich and even “Captain Marvel” to a certain extent, are guilty of building-up modern warfare in that sense, but not to the point of exploitation.

So when those films came out, I experienced plenty of trailers and advertisements from the military as a partnered campaign with the film to increase recruitment.

I loathe modern war films that pretend that war still isn’t awful, which is why I happened to love “The Outpost.” It reminds us, even with the advancements of technology today, that war is still horrifying and taking human life, and watching those around you die is awful to experience.

What caught me off guard about “The Outpost” initially was the lack of story or plotting. But as the film progresses, you find that the entire film is essentially on a countdown, but one you can’t see: the Taliban are coming and you never know when.

And what I found so impactful was how abrupt the attacks were. The film takes what audiences know about scene construction, structure and pacing, and says, “What if during the scene of character interaction, it’s cut off right in the middle with an attack in the dead of night.”

Usually, I am a stickler for structure in film, but in something recent like “1917,” the film is trying to make the audience another character and providing them with this stressful and paranoid experience where you never know what’s going to happen next.

What really helps with that idea was having absolutely no protagonist. The closest we have to one shockingly departs not even halfway through the film. That abrupt exit is a way of telling the audience that nobody is safe here.

There are a handful of characters you do get to know, but none stick out as much as the lead until, perhaps, the very end. The last name of one of the actors does give away his significance in the film, but some of those characters do end up dying because this is a true story — not a Hollywood manifestation.

One other aspect about the characters that I found was terrifically handled was that they don’t feel like movie characters. So often in war films, you get to know them by odd traits — like one has weird glasses, another tells jokes or one takes the photos, another is afraid of combat.

Those elements are there in this film, but so subdued to where I felt like I was watching a documentary, which can be attributed to great direction.

This film also doesn’t trade the emotional trauma of these characters for “badass” action scenes that make America look “awesome.”

In fact, the final scene of this film is one of the soldiers crying in therapy because he did everything he could to save a fellow soldier, but he died while being worked on by the medical unit. When in another film, that soldier would save his friend and the friend would live on and make for a sappy ending.

“The Outpost” just takes all of those familiar elements and twists them into such a pessimistic ideology. If you’ve read my reviews consistently, you’d also know that I hate movies that have the entire final act be one long action scene.

“The Outpost” is two hours and literally the last forty-five minutes is a battle and not one second of it lets you go; you’re biting your nails on the edge of your seat the entire time.

So this director needs a trophy or some kind of recognition for making one of the longest and tense “action” scenes of the last several years. One detail I did find distracting, though, was every time a new character appears on screen a lower third graphic pops up to state their name.

I get what the film is doing by trying to highlight as many soldiers as they can, but the placement of the names felt awkward at times.

This film came out in the middle of summer and nobody really talked about it because of the pandemic, but this film deserves some kind of recognition because I don’t remember the last modern war film I saw that was this good.