Restoring the Fox River’s vitality

‘We used to say that the river was burping’ due to methane levels

February 8, 2023

In 2004, George W. Bush won the presidency, Internet Explorer controlled 95% of the browser market share and Usher, Green Day and Norah Jones topped the music charts.

Simultaneously, one of the most ambitious environmental cleanup projects began on the Fox River, right in the heart of Wisconsin.

“This was one of the largest projects of its kind worldwide,” said Beth Olson, the Lower Fox River Cleanup Project manager for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. “It is considered both a success on its own and a model for how to do environmental work well.”

On Jan. 9, the DNR announced the State Closure process in the Lower Fox River PCB Cleanup Project, effectively marking the completion of the 17-year-long cleanup initiative.

The DNR’s oversight of the project began in 2004, starting along 39 miles of the Lower Fox River and the bay of Green Bay, targeting polychlorinated biphenyl compounds (PCBs) in river sediments. PCBs are toxic chemicals used historically in carbonless copy paper production and recycling.

The DNR said that the project removed 6.5 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment, with the U.S. EPA estimating the cost to be roughly $1 billion.

Cleanup of the toxic materials was completed in 2020 through a collaborative effort between the DNR, EPA, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, select tribal nations and a few corporations, the DNR said.

The Wisconsin DNR listed Georgia-Pacific, Glatfelter Corp. and NCR Corp. as the companies responsible for all work and costs.

The Wisconsin DNR also stated that long-term testing is underway to measure PCBs in fish tissue, sediment and surface water. Recent tests show a significant reduction in PCB levels compared to measurements in 2006 for the upper reaches of the river. Going forward, the entire river and the bay will be tested every five years until the DNR and EPA’s standards are met.

The cleanup initiative now moves into the EPA’s hands, who must deem the work as complete to achieve State Closure.

Polluting the water

The Fox River and its nearby waterways have long been a hub for industrial production essentially going back to European colonization. (The city of Oshkosh, for example, was known as “Sawdust City” due to its expansive lumber businesses that sat along the water.) The paper mills that sprouted up between the late 19th and early 20th centuries were simply the newest players on the block.

But paper production took a dramatic turn in the 1950s when NCR Corp. found a way to create carbonless copy paper, which didn’t cover your hands in ink when you’d use it. The catch? PCBs — which were known to be toxic at the time — were used in its production.

PCBs can cause a whole range of health problems for humans and animals, including cancer, said Greg Kleinheinz, chair of UW Oshkosh’s department of engineering technology.

“The effects on humans and other animals are similar,” he said. “These may include adverse effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and endocrine system.”

Kleinheinz said that the most common health effect of high-PCB exposure is skin conditions such as acne and rashes, although the effects may range depending on the length of exposure.

“Workers exposed to lower levels of PCBs over longer periods have shown likely liver damage,” he said. “However, low-level exposures to PCBs in the general population are not likely to result in skin and liver effects.”

The biggest issue with PCB contamination, Kleinheinz said, is that it travels up the food chain and increases in quantity.

“They build up in living organisms both by uptake from the environment over time and along the food chain,” he said.

The production of PCB-laden carbonless copy paper, now being produced by a myriad of companies, increased in the following decades. The EPA estimated that 700,000 pounds of PCBs were discharged into the river by various paper companies between 1950 and 1960.

Enter retired UW-Green Bay ecology professor Bud Harris. He said that the water quality was “atrocious” when he moved to Green Bay in 1969. The ecology of the area was different, Harris said, and there was methane in the water that would bubble.

“We used to say that the river was burping,” he said. “We would get these large [methane] releases that, if something could ignite it, would explode. It was a condition that was far from what it is now.”

However, not all of the water contamination is due to PCBs, which can’t be seen. The presence of methane and visible contaminants can be chalked up to, among other things, coal pollution, which was largely unregulated in the early and mid-20th century.

The DNR was monitoring water quality throughout the 1970s and into 1979 when PCBs were banned. It was around this time that Harris and his students made a startling discovery.

Harris received a small grant from the DNR to study the Forster’s tern, a fish-eating bird that is endangered in Wisconsin. He was expressly tasked with the goal of assessing the species population across the state.

“In that process, we noticed a differential in reproduction between the colonies in Green Bay and others across the state,” he said. “That alerted us that there may be some problems in terms of the reproductive capacity of the species. That was the clue that something was going on.”

Harris and his students began to look for causes of the disparity between populations. At the time, Harris was coordinating the Sea Grant research program at UW-Green Bay. He was able to negotiate with the leader of Sea Grant for some money to begin investigating what was going on.

“It became our research,” he said. “We saw real differences between the colonies [that were subjected to PCBs and those that weren’t].”

Harris and his students were able to link PCBs to the reproduction disparities, but now something had to be done to address the problem. Harris and his wife — who was working for Sea Grant at the time — organized committees and gathered expertise.

“Our task was to analyze the problem and move toward solutions,” he said. “There was a lot of discussion about how we might remediate the problem.”

Harris said that the paper companies, who provided major funding during this process, sat as representatives and experts on these committees. Through their testing and analysis, they were able to find contamination hotspots.

“Then the question was what we should do about it,” he said, adding that there was a lot of debate over the various methods of containing and removing contaminants. “It took a lot of time to sort out before there was any action.”

Getting involved

Harris and his students were not the first people weary of PCB contamination. The DNR and EPA were already working to understand the issue by the time they were banned, according to Olson.

“Research on PCB contamination in the Fox River, Green Bay and Lake Michigan was underway in the 1970s by scientists working in parallel with universities and other groups,” she said. “PCBs were a concern when EPA banned them and the DNR issued fish consumption advisories for PCBs in fish.”

The DNR, EPA and the state and federal departments of justice oversaw the cleanup work. But finding the key players involved in the contamination wasn’t straightforward, Olson said, as it wasn’t limited exclusively to paper companies.

“Anyone who used or recycled this carbonless copy player, including offices, contributed,” she said. “So there’s a large group of contributors to PCBs in the river.”

A slew of potentially responsible parties was identified, all of whom were suspected of having contributed to the contamination. The list was extensive and included the city of Appleton, the Neenah-Menasha Sewerage Commission, the U.S. Army Corps and even the state of Wisconsin, as the use of carbonless copy paper was widespread.

“There were hundreds and hundreds of contributors,” Olson said. “We were identified as a potentially responsible party because we recycled office paper. And when that paper is recycled, the recycling process discharges it into the river.”

Ultimately, Olson said, three primary companies were identified and tasked with completing and covering the costs for the cleanup: NCR Corp., Glatfelter Corp. and Georgia-Pacific.

“It took a long time to get to just these three companies,” she said. “When there’s a site and we don’t know where the pollution came from, taxpayers pay for it. Ultimately, the goal is to find out who did the polluting. If you can find that out, you can get them to pay for it so that the taxpayers don’t have to.”

Olson said that, when the cleanup first began, many of the paper companies willingly contributed money to begin studies on the river.

“As the magnitude of the project became apparent — 39 miles of river and estimates of $700 million to clean it up — companies started looking at each other, saying, ‘You contributed more than I did,’” she said. “That’s a separate arena where the companies are suing each other for contribution.”

From 1998 to 1999, demonstration projects that removed sediment were conducted and proved successful.

Meanwhile, the EPA proposed adding the Fox River and Green Bay to a list of Superfund sites to be cleaned. However, this fell through and the site was never officially added. Nonetheless, the federal government issued a cleanup order to the responsible parties.

Cleaning the water

Out of the feasibility studies and demonstration projects came three main methods for extracting PCBs, and Olson said that choosing which to use came down to a variety of factors.

“We used sophisticated computer modeling of hydrodynamic forces, and considered sediment stability, ship traffic and other factors including the dynamic interplay of factors in the river system,” she said.

Dredging, capping and sand covering were the three primary cleanup methods used. The DNR describes dredging as the use of hydraulic pumps to move sediment to a processing facility.

Sediment that was brought up and processed was then disposed of via landfilling, which the DNR said it chose due to its efficacy and cost-effectiveness. The sediment was transported to licensed and authorized landfills in Wisconsin and nearby states.

The DNR said that vitrification — the process of turning a substance into glass — was considered, as the high temperatures needed for vitrification would destroy PCBs in the material. The glassy material could then be used in construction projects. However, this option wasn’t chosen due to its size and cost.

In areas where dredging was less practical, capping was used. Capping places various thicknesses and sizes of sand, gravel and armor stone to permanently trap sediment in place. The caps’ designs differ from location to location, but they all completely isolate PCBs from the water.

Sand covers were used for areas with low PCB concentrations, either as the primary method of cleaning or to further clean dredged areas where small, residual amounts of PCBs remained.

The DNR explains the process of sand covering on their website, stating that “the sand effectively reduces the PCB concentration at the surface of the river bottom thereby reducing risk. Special-grade sand is spread in a uniform manner to settle evenly on the river bottom.”

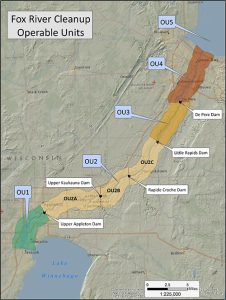

The Lower Fox River was divided into five Operable Units (OUs), based on the geographical and physical characteristics of the area.

OU1 covers the area from Little Lake Butte des Morts to the Appleton Dam and was actively cleaned from 2004 to 2009.

In 2002, feasibility studies were completed. The 2002 feasibility report lists over 2.2 million cubic yards of PCB-laden sediment in OU1.

In 2010, the Remedial Action Certification of Completion was released, effectively certifying the end of cleanup for that area. According to the report, the total cleanup cost for OU1 was just over $96 million.

The DNR reported that 372,000 cubic yards of sediment were removed and 114 acres were capped in OU1 during the cleaning period.

Cleanup efforts for OUs2-5 ran from 2009 to 2020. OU2 covers the area from the Appleton Dam to the Little Rapids Dam, OU3 from Little Rapids Dam to the De Pere Dam, OU4 from the De Pere Dam to the mouth of the bay of Green Bay and OU5 covers the bay of Green Bay.

Monitored natural recovery — which utilizes natural chemical and biological processes to contain and reduce contaminants — was chosen for most of OU2 and OU5.

Dredging, capping and sand covering were used for OU3, OU4 and parts of OU5 near the mouth of the Fox River into Green Bay, where more than 6 million cubic

yards of sediment were dredged and roughly 850 acres were capped or sand-covered, according to the DNR.

A variety of companies were involved in the actual cleanup efforts. Boldt Technical Services, a subdivision of The Boldt Co., served as the primary oversight contractor for the DNR, and the engineering company Ramboll worked as Boldt’s subcontractor. The marine construction firm J.F. Brennan Company was the project’s dredging contractor.

But even with plans in place and a stew of companies capable of cleaning the water, remediation was anything but straightforward. Legal battles ensued throughout the cleanup’s lifespan, including the use of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA).

NRDA is a legal process that federal agencies, states and American Indian tribes use to assess the impact of oil spills and hazardous waste sites, among other things.

The Fox River Trustee Council — consisting of the DNR, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — has utilized NRDA to recover $90 million from settlements. The recovered funds have been used to ameliorate PCB-related injuries to wildlife and the environment.

In a 2011 progress report, the Fox River Trustee Council stated that “cleanup activities reduce risks to human health and the environment, but do not necessarily restore natural resources, which is the objective of the restoration activities undertaken by the [project] Trustees.”

Many of their projects have enhanced or created nesting spots for Forster’s tern and other birds affected by PCB contamination. Fox River Trustee Council Restoration Coordinator Trina Soyk said that NRDA funding has enabled more than 200 restoration projects through the Fox River Trustee Council.

“These projects range from habitat protection, wetland restorations and fish population enhancement projects to public use projects that provide access to fishing,” she said.

But even outside of NRDA and the Fox River Trustee Council, lawsuits abounded. Olson said that, between 1997 and 2019, there were 22 milestone legal cases.

In 2012 and 2013, for example, Olson said that the court held the three paper companies liable for cleanup and government oversight costs after an 11-day trial.

“We went down to Milwaukee for the trial because the courtroom in Green Bay wasn’t big enough for all of the attorneys,” she said.

Despite the legal battles, Olson said that everyone did their part in the end.

“We had to have catalysts for movement every now and then,” she said. “But we got it done together.”

Moving forward

In 2017 and 2019, the DNR reached pivotal agreements with the three cleanup paper companies that nearly pushed the project to the finish line, Olson said. The three companies — NCR Corp., Georgia-Pacific and Glatfelter Corp. — were mandated to cover all remaining costs by a federal judge, Wisconsin Public Radio reported. These include long-term monitoring costs.

Active cleanup was marked as complete in 2020.

The DNR’s website states that “starting in 2022, all OUs will be sampled in one event and then every five years thereafter to be on the same monitoring schedule throughout the system and to coordinate with EPA’s 5-year review cycle for this project.”

As part of the State Closure process, the DNR mailed notice letters to 1,400 riverfront property owners informing them of the project’s completion and requesting final closure. Also, those receiving notice letters are being informed of cap areas, and are asked not to disturb them.

Moving forward, the DNR said long-term monitoring will be conducted to evaluate fish tissue, surface water and sediment. The integrity of the caps will also be monitored.

Olson said that the project was a major success and that it wouldn’t have been possible without cooperation from everybody.

“This project has been going well for over 20 years, from planning, through implementation and now the monitoring phase,” she said. “Each year, the EPA and DNR requested a ‘lessons learned’ session attended by experts from all parties involved in the cleanup. This effort smoothed the way for the coming year by learning from what went well and what could’ve been done better in the prior year’s work.”

Olson said that the legal action required by this project was an area that could have been improved.

“Litigation is one workload area that could have been reduced if there had been more voluntary compliance,” she said. “But a project of this size and scope is complicated.”

Overall though, Olson said that this project speaks volumes about what can be done for future projects on the Fox River, including addressing other forms of pollution.

DNR monitoring has reported PCB reductions of 90% in river water and 80% to 90% in sediment since 2006. Additionally, PCBs in walleye average 65% lower and are approaching the “unlimited consumption” advisory level, which the DNR said is a critical milestone.