‘The Trial of the Chicago 7’ provides cutting commentary

November 4, 2020

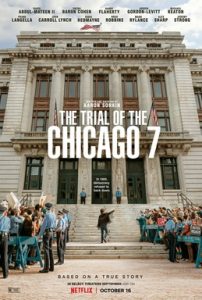

“The Trial of the Chicago 7” is the latest Netflix film to attach high-status talent. Later this year, it will be David Fincher; however, in the writer/director chair here is Aaron Sorkin, who is one of the most decorated writers working today.

This is the true story of the seven people on trial stemming from various charges surrounding protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

This is quite an interesting film because when the film started, almost immediately I

thought, “this film is quite on-the-nose so far. It feels like this should be a Spielberg drama.” Coincidentally, I was right.

The DreamWorks Pictures logo was the first tip that this was tied to Spielberg because the thing about Spielberg nowadays is that he’s like a vulture when he looks for new projects.

Someone will write a script, it will climb the ladder and if Spielberg doesn’t want it, he tosses it back down the ladder. However, this time, Spielberg left the project back in 2007 because of the writer’s strike. So the project was shelved until 2018 with a theatrical release in mind until COVID-19 happened, which caused the film to premiere on Netflix.

The fact that this film was greenlit in 2018 feels like no coincidence because this film does not shy away from political commentary. I would highly suggest reading up on the “Chicago 7” before seeing the film — although the film does an adequate job at explaining them — it’s a film about a handful of left-wing protesters who are cuffed and courted for protesting Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon’s handling of the Vietnam War.

The phrase “Let’s bring back the good old days” gets thrown around by elderly, right-wing white men a lot as well. So Sorkin is clearly mirroring the present through the past.

Amidst the sea of B-movies that have been keeping this year afloat, it was genuinely entertaining to see a film made on this scale by quality talent, and I don’t just mean Aaron Sorkin, but Eddie Redmayne, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Michael Keaton, Mark Rylance and Sacha Baron Cohen.

Though the runtime was tedious to bear at times, the cast and their performances kept the film chugging — Redmayne and Rylance. Baron Cohen is who I was most excited to see just because I think he’s a good actor in general besides doing wacky characters, but he was okay in this film.

The most impressive part of the film was hearing Redmayne’s American accent. His character takes the forefront of the other protesters on trial because he’s the most eloquent speaker, which creates a rivalry between his character and Baron Cohen’s because, within these seven protesters, all of them have their own niche.

Baron Cohen represents the hipsters, Redmayne represents the uptight, political college student and Yahya Abdul Mateen is a part of the Black Panther group. So these seven people on trial are a microcosm of the leftwing youth movement of the late ‘60s.

In a narrative sense, Sorkin decides to play the entire film in the courtroom over the course of one-hundred and fifty days while intercutting the inciting incidents that got the seven into court — debating whether it was the police who incited violence on the protesters or the protesters on the police.

Like most suitand-courtroom films, there is little through-line to the film so it does feel like you’ve dropped anchor for several minutes every once in a while, which leads to pacing issues.

However, one thing I did enjoy about Sorkin was his dialogue. Film is obviously not reality, so there are some who believe that polished dialogue that nobody would ever say is best for a film, but when one makes a film based on real events, it does sound odd when the hippie has witty banter with the preppy college student.

However, I looked past that early on because I appreciate polished dialogue though it’s a case-by-case thing. But what I did find odd was Sorkin’s choice of tone because this film does several one-eighties.

One of the first scenes is a character catching a thrown egg from an angry mob and they just sort of have it for a while. Then the Judge is introduced, and he’s a little funny by continually establishing that he has no relation to Baron Cohen’s character.

The lighter elements were fine as long as they were character-based, but the bit with the egg was so useless.

The ending as well was quite “movie.” It’s this big dramatic scene, which is why I thought this should have been a Spielberg film because I found several similarities to “Amistad” and how that ending was so schmaltzy Spielberg. So I could feel his shadow looming over this film.

However, I did like the ending as I thought it left you on a high note.

There feels like a more efficient way to tell this story, but the one we got was pretty good considering the thirteen credited producers.

This film is a way for Sorkin to mirror America today through the past which makes the present easier to interpret, hence why westerns are so uniquely “American.” So by telling this particular story, Sorkin is clearly pointing out how history is repeating itself. It doesn’t feel so much like he’s taking a stance but simply giving people a framing device to step back and see the bigger picture.