Geology lecture reveals nature of Wisconsin

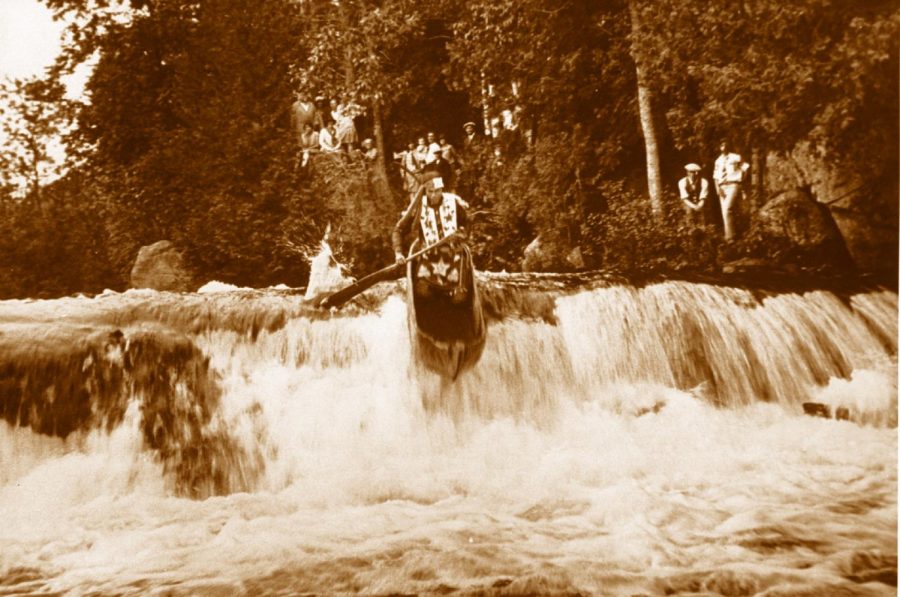

The dugout canoe descending the fall above was held in UWO’s viewing room for years and recently donated to UWSP.

The Director of the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point Museum of Natural History gave a lecture in Halsey Science Center on Friday to round out the three-person speaking series hosted by the geology department and Geology Club.

Ray Reser covered 32 PowerPoint slides worth of information about weathering the ice age and how Wisconsin has rebounded from it to become the state we know today.

He talked about a North American ice-free corridor that was once thought of as an open passageway from Northwestern Canada to the western edge of the United States, how it is no longer thought of that way and what that means for our state.

He talked about animal bones and their versatility, how they were used for fishing hooks, hair combs, drinking bowls, weapons and more.

Reser expressed gratitude to a former UW Oshkosh artifact that was given to UWSP, one of North America’s best-preserved dugout canoes.

Clovis projectile point (arrowhead) presented above: “Silurian Chert found ~ 1907 Waupaca Co. WI” Director UWSP Museum of Natural Hisory Ray Reser.

He talked at length about the mounds of Wisconsin. Reser said he has been to over 2,000 mounds, and only about five of them were untouched before he got there. He even pointed out a quote from President Lincoln about the mounds of our nation holding giants.

Reser closed his presentation with a remark about archaeology being the slow accumulation of knowledge about our shared past.

UWO professor Eric Hiatt said Reser thoroughly explained how the last ice age had a substantial effect on Wisconsin.

“Dr. Reser provided an excellent framework that linked climate change and the early human history of Wisconsin,” Hiatt said. “He pointed out that not only was Wisconsin’s landscape primarily shaped by the Pleistocene ice age, but these climate changes led to changes in wildlife.”

Reser said early humans first migrated into Wisconsin about 14,000 years ago, which he said is now thought of more factually, based on the latest DNA evidence.

Hiatt said Reser explained the way early American culture evolved from nomadic hunters of woolly mammoths, mastodons and caribou at the end of the ice age, to settled farmers who hunted whitetail deer and small game about 1,000 years ago.

Hiatt said every bit of Reser’s presentation exhibited the way people were impacted by severe climate.

“Reser documented the evolution of stone tools, ancient trade networks and the development of ceramics in Wisconsin, which highlighted the possible migration pathways into North America, which were also linked to changing climate, which shows that human migrations and development of cultures is closely linked to geologic processes that impact the environment,” Hiatt said.

UWO professor Timothy Paulsen introduced Reser to the audience and said Reser’s lecture exemplified the way people lived in a time when glaciers covered the land.

“It wasn’t too long ago, geologically speaking, that glaciers covered a good part of our state,” Paulsen said. “But based on Ray’s work and other work that Ray covered, we can start to get an idea of how people were feeding themselves and what they were doing around the time glaciers were retreating from Wisconsin.”

Paulsen said the fluted Clovis points (arrowhead stones) Reser presented were interesting because of the way early Americans adapted to their geologic resources and in effect made life more comfortable. He said the way archeologists have traced the dispersion of those stones is just as interesting.

The fluted Clovis points Reser presented were hollowed, either throughout the core of the stone or just at the base, and mounted flush to a piece of wood or bone to make a weapon, Reser said.

Reser said ancestral Native Americans would carry many spears in the same way that hunters today carry many rounds of ammunition.

Clovis projectile points presented above: “Hixton Silicified Sandstone, found ~ Richland Co. WI 1897 (WI state vertebrate fossil);” Director UWSP Museum of Natural Hisory Ray Reser.

Paulsen said the way we use our geologic resources today is similar to the way Native Americans used them thousands of years ago.

“As people today, as Wisconsinites today, we still use our geologic resources, maybe not the same ones, but we rely on geologic resources throughout the state,” Paulsen said.

Reser was invited to speak at UWO after the geology department noticed a Tap Talk he had given earlier this year.

The Tap Talk Facebook event post said Reser revealed “abundant evidence that Native Americans were tracking the edge of the North American glacial ice sheet as it advanced and retreated through our area, eventually exploiting rapidly changing ecosystems in the post-glacial landscapes that became the region we call Central Wisconsin.”

The geology department asked professor Jeffery Behm if he had heard of Reser, and Behm said he had.

“I’ve known Ray for decades; we were undergraduates at the same time,” Behm said. “I’ve worked with him, dug with him, known him better than most archeologists in the state.”

Behm said he gave the old dugout canoe to Reser as soon as Reser was done with graduate school in Australia and became director of the museum at UWSP.

Behm said it is a well-known canoe that was manufactured sometime in the early 20th century, possibly in the 19th century.

There are many marks Reser pointed out on the canoe that make it distinguishable; such as, indentations on the bow.

Behm said the canoe will soon be transferred to the museum of the Menominee. Behm said he has been working on a dugout canoe research paper with Reser for a while and that this canoe is one of the best in the state.

“Most of the canoes are flattened by the weight of water and sediment or badly cracked and missing a bow or a stern,” Behm siad. “This one is complete enough that we can get measurements and architectural drawings.”

Behm said this dugout canoe is similar to the dugout canoe displayed in the Smithsonian museum, and they were possibly made by the same person.

Behm said what Reser presented and expanded upon on Thursday was the old idea that ancestral Native American people had an open passageway to migrate south into North and South America from the now submerged Beringia.

The open passageway is now known to have been closed for thousands of years, leaving people trapped and unable to migrate, Reser said.

Clovis projectile point presented above: “Hixton Silicified Sandstone found ~ Jackson Co. WI” Director UWSP Museum of Natural Hisory Ray Reser.

Reser said people migrated in waves and the first settlers who made it through the passageway before the ice froze over migrated along the coast to the south where the ice sheets didn’t reach.

Reser said it wasn’t until thousands of years later that the ice melted and people were able to migrate again, this time being able to migrate into the cleared Great Lakes region.

Behm said this all furthers the debate about how people got here.

Behm said there are four ideas of how people got to North America and Wisconsin, but said the earliest and most undeniable idea is the coastal colonization from Eurasia.

“The genetic evidence all suggests that people came from Eurasia,” Behm said. “There is no genetic evidence of people coming from sub-Saharan Africa.”

Behm said Reser presented an information-packed timeline of Wisconsin’s evolution as a state in his hour and 20-minute lecture. Behm said all that information could be applied more broadly to our region.

“It was a really good summary of 14,000 years of human occupation in Central Wisconsin,” Behm said. “He looked specifically at Central Wisconsin, but it’s a pretty good representation of the upper Midwest.”

Criminal justice major Dylan Ott said he liked the developments Reser presented about early settlers migrating our continents.

“I liked the new information he had about how people got to North and South America,” Ott said. “I also liked how they think people came from all over, instead of migrating just the land.”

Criminal justice major Ryan Kaul said Reser presented good facts and a fluid presentation.

“He went from one time period to another without throwing it all together at once,” Kaul said. “He had good information about how people would hunt and the evolution of hunting from spear to bow to arrow.”