Criminally Charged

Richard Wells

Former UW Oshkosh Chancellor Richard Wells and former Vice Chancellor of Administrative Services and Chief Business Officer Thomas Sonnleitner face five counts of misconduct in office for illegally transferring money to the UWO Foundation to help pay off loans. They could face more than 16 years in prison each if convicted.

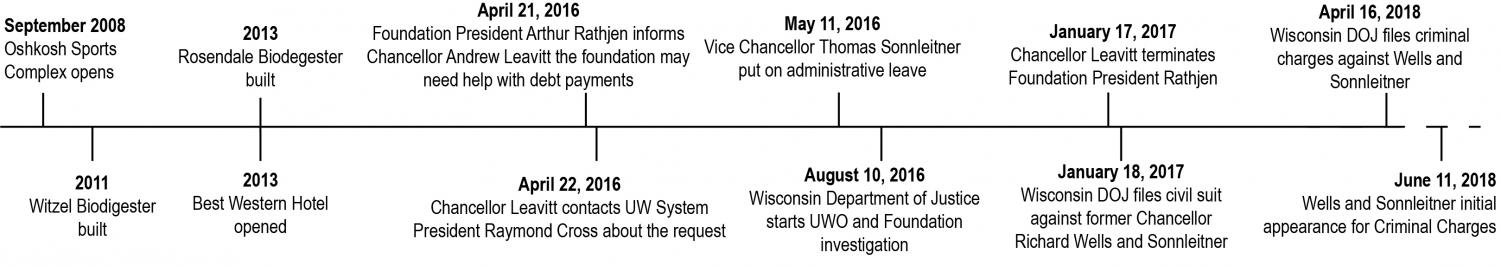

On April 16 the Wisconsin Department of Justice filed criminal charges against Wells and Sonnleitner. According to the criminal complaint, Wells and Sonnleitner are being charged for improper financial transactions that occurred under their former administration from 2010-2014 related to five real estate projects.

Wells’ lawyer Raymond Dall’Osto said his client had good intentions.

“Richard Wells and I are saddened that the Attorney General’s office has chosen to issue criminal charges against him, based upon memoranda of understanding, loans and undertakings through the UW Oshkosh Foundation, which were intended to benefit the University,” Dall’Osto said.

In January 2017, the Board of Regents and UW System asked the DOJ to pursue civil charges against the two former administrators.

Tom Sonnleitner

According to online court records, both parties will make their initial appearance June 11 in Winnebago County Court.

According to the criminal complaint, the two administrators funneled $11 million in taxpayer money into five Foundation building projects including, the Best Western Premier Waterfront Hotel in downtown Oshkosh; the Alumni Welcome and Conference Center; two biodigesters, which turn animal waste into electricity; and the Oshkosh Sports Complex, which includes Titan Stadium.

The complaint details claim Wells and Sonnleitner signed financial guarantees involving five of the Foundation’s building projects that exceeded their authority as Chancellor and Vice Chancellor. Both parties made guarantees that UWO would cover additional expenses while knowing there was no additional money available.

A document signed by both parties, called a “Memorandum of Understanding,” states “If the revenues from the operation of the Facility are insufficient to service the operational budget and debt service on the loan, that the University will cover any deficit that is incurred by the Foundation in support of the operations of the Facility and the payment of debt service. The University will also fund any sunk costs incurred by the Foundation if the facility would not be completed.”

The criminal complaint says:

- Wells and Sonnleitner signed guarantees for the hotel project in which UW Oshkosh agreed to cover “any additional investment loans and expenses” as well as a $7.5 million loan from First Business Bank, if the Foundation was unable to make payments.

- Wells and Sonnleitner signed guarantees for the Rosendale Dairy digester in which UW Oshkosh agreed to pay any deficit if revenues from the facility didn’t cover the costs and debt service. Sonnleitner also made a guarantee to Wells Fargo Bank in which UW Oshkosh agreed to hold $10 million in state funds as unrestricted assets to guarantee to cover a loan used to pay for construction.

- Wells and Sonnleitner signed guarantees for the UW Oshkosh campus biodigester in which UW Oshkosh agreed to cover a $3.7 million loan from Wells Fargo Securities if the Foundation couldn’t make the payments. They also signed guarantees in which the University agreed to pay any deficit if revenues from the facility didn’t cover the costs and debt service.

- Wells and Sonnleitner signed guarantees in which UW Oshkosh agreed to cover any deficit incurred by the foundation to support the Alumni Welcome and Conference Center. UW Oshkosh also agreed to to pay the Foundation on an annual basis for any cost overruns for the project. Sonnleitner also made guarantees to Bank First National in which UW Oshkosh agreed to cover a $10 million loan if the Foundation couldn’t make payments.

- Wells and Sonnleitner made guarantees on behalf of UW Oshkosh related to the Foundation’s obligations for renovation of the sports complex. UW Oshkosh agreed to pay “in the event any donors would default on their pledge payments” for pledges written off as uncollectible until the bond is retired this year.

Board of Regents Audit Committee Chair Michael M. Grebe issued a comment in the criminal complaint explaining why criminal charges were pursued.

“Last year, the Board of Regents and UW System asked the Wisconsin Department of Justice to pursue civil and criminal charges against two former campus leaders who broke the sacred trust they carried as public UW officials,” Grebe said. “The Board took this unprecedented action because Dr. Wells and Mr. Sonnleitner failed to follow rules and statutes that govern University operations, and we are working diligently to rebuild confidence in our institutions and to improve the transparency of foundation transactions. We support these charges by DOJ and will continue to seek justice in this case while serving students with integrity and transparency.”

Sonnleitner’s lawyer Steven Biskupic responded to inquiries with, “We respectfully will be making no comment on this matter at this time.”

UWO Chancellor Andrew Leavitt sent students and staff an email on April 26 in response to this news, stating the University is focusing on moving forward and to “exemplify resilience through stewardship.”

Leavitt responded with a no comment statement to further questions.

“Current litigation prevents me from making comments about the criminal, civil or bankruptcy proceedings,” Leavitt said.

The UW System and UW Foundation directed comments to the DOJ.

Dall’Osto said he is unaware of how long it could take before there is a verdict.

“I don’t know how long it will take to wrap up this case,” Dall’Osto said. “But, right now we are in between the filing of the criminal complaint and the first hearing.”

The charges that have been filed are felony charges. In Wisconsin, the first step is the issuance of the criminal complaint. Then there is an additional court appearance, which is scheduled for early June. After that, in a felony case, a preliminary hearing, also known as a probable cause hearing, is scheduled. The next step in the process is what is called an arraignment, the formal entry of a plea, where a not-guilty plea can be entered. Once the arraignment takes place then the government or prosecution has a duty to turn over what is called discovery.

Dall’Osto gave examples of what a discovery in this case could include.

“In this type of investigation would be investigative reports, it might be documents in correspondence from various parties, the foundation, maybe the bank’s involved, University and the defendants,” Dall’Osto said.

The discovery phase, depending on how much is there, can last anywhere from a couple months to well beyond depending on how complex the case is.

“Given what is all out there and what I’ve seen in the civil case, this would be considered a complex case,” Dall’Osto said.

The next steps include motion hearings, which could be a motion to dismiss it, to suppress it, keep out evidence or it could be a motion to compel more discovery. After the motions are done, then there is a final pretrial hearing. At that time, the court is advised by the parties if this case is on track for a trial or if there is going to be a resolution.

Dall’Osto commented on why it took the DOJ a year before moving forward with charges.

“I don’t know why,” Dall’Osto said. “Mr. Wells and I were saddened and disappointed that they had moved ahead and filed charges.”

According to Dall’Osto, the case could play out in five different ways.

“It could play out by, number one, being dismissed,” Dall’Osto said. “It could play out by, number two, some form of deferred prosecution. It could play out by, number three, going from a defense perspective best to worst, a resolution on different charges. Number four, a resolution on fewer charges, and number five, a resolution on the same charges.”

Local Attorney David Sparr gave his professional opinion on the case.

“I’m guessing [Wells and Sonnleitner] thought it was a good idea at the time, having a nice hotel for everyone to stay in, having these other projects going on that give the whole school a good reputation,” Sparr said. “I think any administrator would like to have these things and I’m not saying they did, but maybe they just went too far.”

Sparr said he doubts that each defendant will receive three-and-a-half years in prison per count.

“To me, it seems like a case for probation at most because they usually look at, ‘Is somebody financially benefiting from this?’,” Sparr said. “It kind of surprised me what the prosecutor did, actually.”