Police suicide numbers rise

Photo courtesy: Wisconsin Game Warden Magazine

A line of police cars can be seen in the side mirror during rush-hour traffic on I-94 in Milwaukee. The road was shut down to honor a Milwaukee officer killed on duty.

University Police Chief Kurt Leibold experienced 12 officer suicides during his 26 years as an officer and assistant chief of police in Milwaukee.

One officer was dealing with the stressors of his job as well as planning a wedding. Another was unsure if police work was the right line of work for him personally. Many officers had difficulty dealing with all the hard cases they saw.

Leibold said he knew many of the officers, and most of their suicides were completely unexpected.

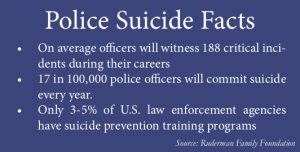

But those suicides shouldn’t be unexpected, according to a study done by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a private philanthropic foundation based in Boston.

The 2018 nationwide study found that first responders, which includes law enforcement officers, firefighters and emergency medical service personnel, are more likely to die by suicide than in the line of duty. In 2017, for example, 140 police officers committed suicide, while 129 officers died in the line of duty.

Leibold said while he experienced 12 officer suicides he knew only three officers that were killed on duty.

The study also found that post-traumatic stress disorder and depression rates for first responders are as much as five times higher than the rates of other citizens.

Other research gives more detail into the problem:

— A 2013 study of 750 police officers found that exposure to critical incidents had a direct correlation with alcohol and post traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

— Other studies estimate that 35 percent of officers suffer from PTSD symptoms, and 9-30 percent suffer from depression.

Those statistics hit close to home earlier this month when a UW Oshkosh police officer shot himself in the torso during a domestic disturbance.

“He’s been serving the public for 25 years,” Leibold said. “He’s been a public servant, and he’s done a pretty good job, and he just had a crises.”

Leibold said there are many stressors that could contribute to poor mental health with police officers.

“Police officers work nights, they work weekends, they work long hours and holidays. It’s not a healthy environment,” he said. “They eat on the run, rarely do [they] get to sit down … and have a meal or plan a lunch; it’s always when you can get it in.”

For some, the stress is too much.

Leibold said an officer he was close with approached him with concerns when he was a sergeant in Milwaukee. The officer was about three years into police work in a busy district.

“He saw a lot of bad stuff and had to deal with a lot of bad stuff,” Leibold said. “I remember he was in a transition in his life and he came to me wondering, ‘Is this the job for me?’ I encouraged him and said, ‘Yes, police work has ups and downs.’ We’re struggling in this industry getting quality people who want to do this type of work, so I encouraged him … to keep pushing forward, because we need people like him to do police work.”

One year later, the officer took his own life with his service weapon.

Leibold says he still feels some guilt about that officer’s suicide, and he wonders if he pushed the officer to stay in the profession when he was asking how to get out of it.

“That one hurt a lot, but in hindsight, we can always look back and see some signs,” Leibold said. “But it’s too bad we didn’t do interventions when it was happening to make a difference.”

Leibold said he knew another officer was struggling with mental health when he was in the process of planning his wedding. That officer didn’t approach Leibold for help.

“I don’t know if that stress put him over the edge,” Leibold said. “The stress of a wedding, the stress of a job, but he ultimately ended up killing himself, too.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, police work has one of the highest rates of injuries and illnesses out of all careers due to high-risk situations.

Kate Mann, Oshkosh crime prevention and public information officer, said she agreed that there are many things that make police work stressful.

“The things that we see on the street, usually people don’t experience in their lifetime,” Mann said. “We see a lot of different situations in people [who] are not having their best days and that can be tough — all the different calls we have to experience, whether it’s a suicide, an accident, a domestic elder abuse, animal abuse, there’s so many different scenarios out there.”

Leibold said police work is different than any other kind of work except maybe military.

“I say that because you never know what’s going to happen,” he said. “You can go from driving down the street and being 100 percent calm, to seconds later being 100 percent adrenalized. Physically, it takes its toll.”

Leibold said over time, he’s noticed that there has been more awareness in precautionary measures toward mental health.

For example, UWO officers are encouraged to attend emotional survival training provided by national instructors.

“It’s sporadic,” Leibold said. “It’s not something that’s required, not something that probably there is enough of. Different police departments do different things. Some are way ahead of the curve as far as mental well-being for their police officers.”

Mann said the Oshkosh Police Department holds in-service training twice a year, rotating training on different topics, including education on mental health. Training could also include how to deal with stress.

“One of the things that is common for law enforcement is to exercise,” Mann said. “It’s a good stress reliever and it helps keep us in shape for our job. And then in the past we’ve [also] talked about making sure you have a healthy diet, that you get enough sleep … the usual things that are discussed to help relieve stress.”

Leibold also said the University screens officers’ mental health through a psychological exam as a requirement. Mann said the Oshkosh Police Department does as well.

“It is about three hours worth of test-taking, answering different questions,” he said. “There’s an essay portion to it and then an interview, so it’s about a five-hour day.”

Leibold said interventions are also important for officer mental health.

“We have gotten better at having interventions for our own police officers,” Leibold said. “In Milwaukee there was an early intervention program that would flag if an officer called in sick a lot or if they had a lot of citizen complaints.”

Mann said at least half of the Oshkosh Police Department has had a five-day, 40-hour week crisis intervention training.

“That has scenarios in it and just helps teach us about mental health and dealing with people in a crises,” Mann said.

Cole Dawson, a junior criminal justice major, said he plans to be a police officer after graduation and eventually a detective. Although he knows the job is highly stressful, he also knows it is the right career for him.

“Officers work in very stressful situations and sometimes witness horrible cases that take a toll on them, which results in poor mental health,” Dawson said. “I think officers in urban areas would have more mental health issues, the reason being that they usually have higher crime rates, which results in more serious and traumatic cases. Although these rates are high, the job has many rewards, such as helping people and bringing structure to society.”

Leibold said he hopes to become part of the solution to officer mental health problems, and he is now in a master’s program to become a mental health counselor for police officers.

“It’s not only helping them through their careers, but it’s also vetting them on the front end so you get the right people doing police work,” Leibold said. “It’s really important for our future.”

And it’s the right move for him, too, at this point in his career. “… It’s funny because you never know which way your life is going to take you,” Leibold said. “You really don’t.”