The eclipse

Monday’s solar eclipse was visible at least partially across most of the US, but the line of totality for this eclipse was a roughly 100-mile-wide strip running from Texas to Maine.

A total solar eclipse starts and ends with a partial eclipse, just like what was visible in Oshkosh. What makes it different is the short period of totality in the middle.

During a partial eclipse, you must keep your glasses on to safely view the moon passing in front of the sun. But when totality hits, you can take your glasses off and see what appears to be a big hole in the sky, surrounded by the sun’s corona (streams of plasma racing out of the sun’s atmosphere).

The period of totality can also have strange effects on nature and wildlife. An eclipse happening at all is a lucky phenomenon; the sun just so happens to be roughly 400 times larger than the moon, and 400 times further away from us. This means that when they line up in the sky, sometimes it happens perfectly enough that it blocks out the sun and offers us a view of cosmic gases we normally can’t look at without equipment.

Other types of eclipses include annular eclipses, which happen when the moon is further away during a solar eclipse and doesn’t fully obscure the sun. This results in a “ring of fire” effect instead of a period of totality. There are also hybrid eclipses, which happen when an annular eclipse transforms into a total eclipse midway through due to the curvature of the earth.

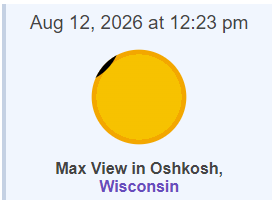

If this eclipse left you wanting more, you have options. If you’re willing to travel, your next chance at a total solar eclipse is on August 12, 2026, almost 9 years after the August 21, 2017 eclipse. It will be visible from the Arctic, Greenland, Iceland, Spain and Portugal. Several cruise lines are even planning special cruise trips on the line of totality.

But if you want to stay closer to home, the next total solar eclipse visible from the US won’t be until 2044.

The 2026 eclipse will be partially visible from Wisconsin, but you probably won’t notice; only a sliver of the moon will interrupt our view of the sun.

The 2026 eclipse will be partially visible from Wisconsin, but you probably won’t notice; only a sliver of the moon will interrupt our view of the sun.

Traveling to the eclipse

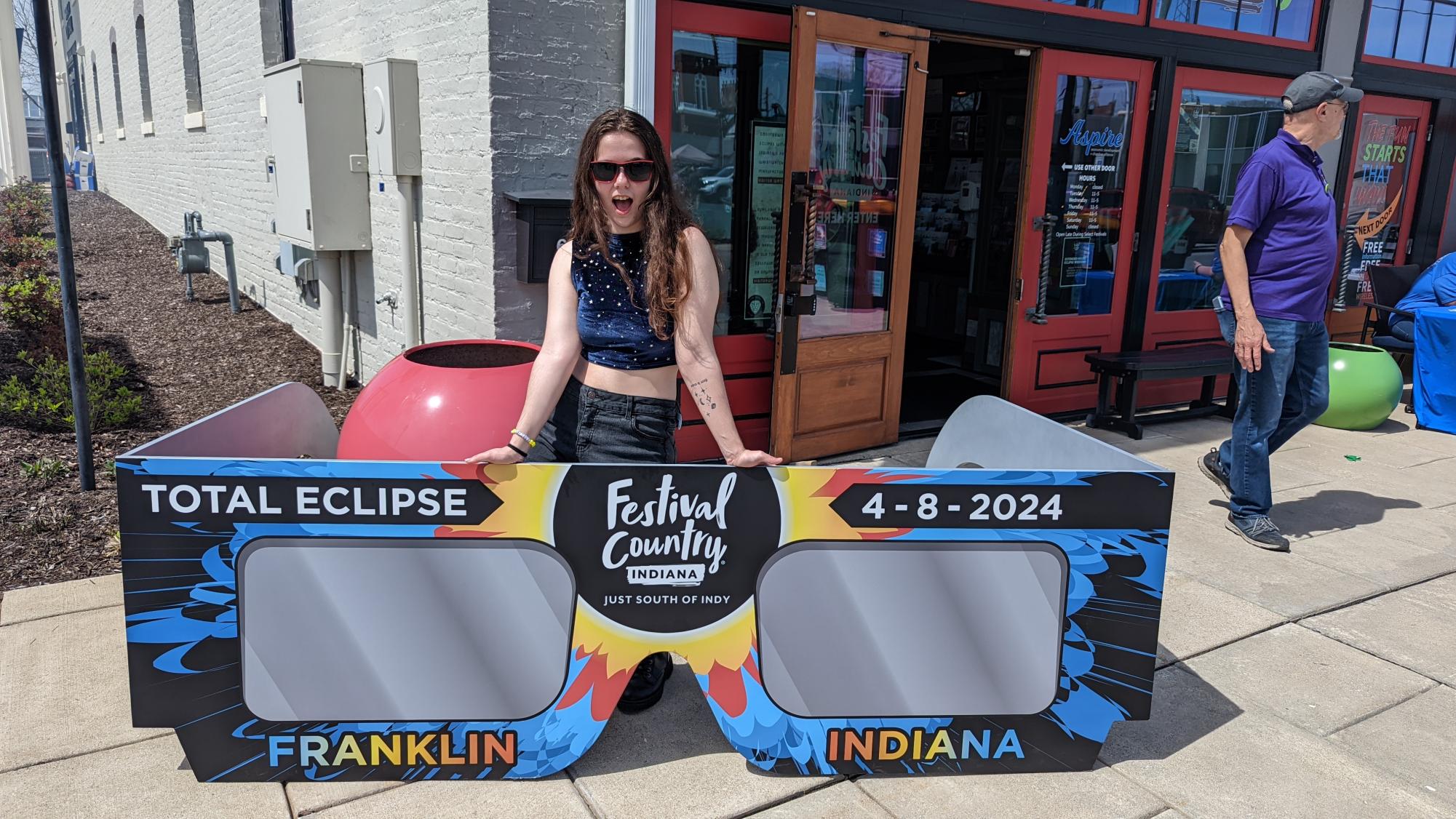

I drove six and a half hours to Franklin, Indiana, a festival town on the outskirts of Indianapolis to view the eclipse. The signs referencing the eclipse started along the way in Chicago, warning travellers to “Fuel up, arrive early, stay put, leave late.”

The threat of cloud cover makes any eclipse trip nerve wracking, and Sunday night didn’t look promising. The wind rocked my tent, pulled the stakes out of the ground, and risked blowing the rain cover away and letting the coming rain in. I decided to car-camp on Sunday night and woke up to the clearest sky I’d ever seen. It was complete luck that afforded me a cloudless view of the eclipse.

However, less lucky was that charging two phones and powering two heated seat covers was too much for my car’s cigarette lighter, and the fuse popped under the steering wheel. Nobody, including the employee at the AutoZone, was able to pry the blown fuse out of my car to replace it, so I had to buy a portable charger and plug it in at a pavilion bathroom to power my phone.

The math homework I was supposed to do on the way home had to be deprioritized to save power for the GPS on the drive back home, which took nine and a half hours with traffic and pit stops.

So, my tip if you’re planning a road trip for the next “Great American Eclipse”? Listen to those street signs and stay late. We left Indy at 5 o’clock in the afternoon and didn’t arrive home until 2:30 a.m.

Eclipse fun

The fun of being in the path of totality doesn’t end with the sun and moon. Franklin, like many of the towns along the path of totality, took advantage of the eclipse to host eclipse programming, though I was disappointed when the scheduled NASA speaker didn’t make an appearance.

Unlike other towns, however, Franklin is used to doing festivals; they’re part of Festival Country Indiana, a project bringing together tourist destinations “just south of Indy” in Johnson County. The town was prepared for tourists with walk-in eclipse tattoos, market tents and grill-outs. At the eclipse festival people sang karaoke to the crowds, got snacks like snow cones and lemon shake-ups from food trucks, and got free eclipse glasses, which were plentiful throughout the event.

2017 versus 2024 eclipse

During a total solar eclipse, the world transforms from day to night in an instant. In 2017, when I saw the total solar eclipse from Nashville, it got eerily still and quiet as the birds stopped chirping and the cicadas started buzzing. Insects swarmed the streetlights, squirrels scrambled into the trees and a nighttime chill almost distracted from the view. The whole city was swept into darkness as the moon’s shadow swept across the Earth.

So in Indiana, I prepared. I brought out my sweatshirt, rolled up the windows on my car to keep the bugs out and readied for the transformation.

But my experience in Indy was different. People cheered as the last bits of sunlight eked out, and the sticky heat lifted from the air and gave the eclipse the spotlight. But the birds continued gentle songs and the scene wasn’t overrun with insects.

The diamond ring, a bright shine that forms as the last remnants of the sunlight shines through the valleys on the moon, took me by surprise and stole the show. I knocked the eclipse glasses off my partner’s face to make sure he saw it, too. I must’ve seen it in 2017, but going to see it as an adult let me see all the things I had forgotten or was too overwhelmed to see when I was younger.

While I was trying to take pictures of the eclipse through my glasses during totality (view the total photo on the left), one of the employees from the bar nearby handed me a solar filter.

It was a shock to park in the parking lot of a bar that I wasn’t patronizing during a tourist event and be treated like a friendly neighbor. I found Festival Country Indiana an apt term for the area and it was lovely to view the eclipse there.