Black Thursday Remembered: 50 years later

Courtesy of UW Oshkosh Archives

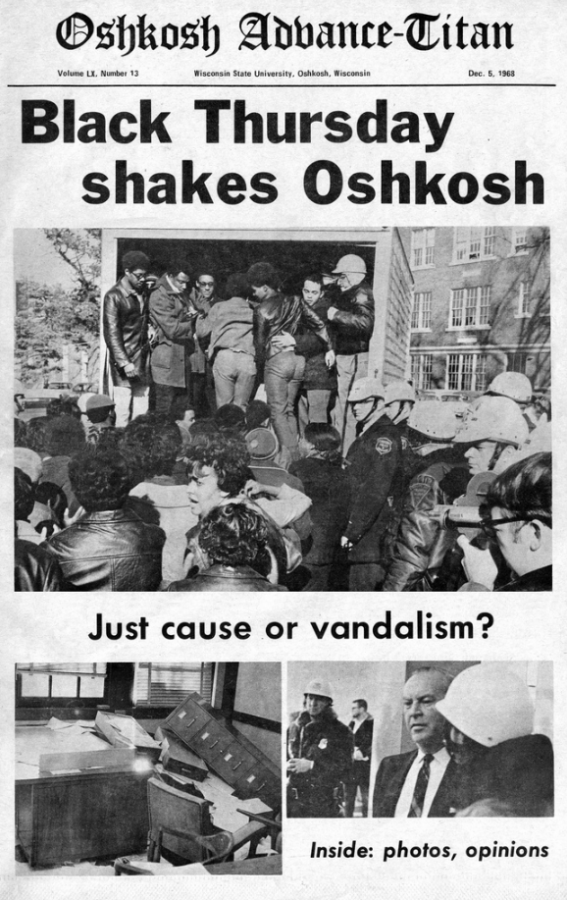

The front page of the Advance-Titan on Dec. 5, 1968, after Black Thursday.

On Nov. 21, 1968, 94 African-American students attending what was previously known as the Wisconsin State University at Oshkosh demonstrated for racial equality on campus.

That morning, the students marched into University president Roger Guiles’ executive office with a list of demands to alleviate the problems many African-American students were facing on campus. 90 of the students ended up being arrested and imprisoned.

Black students had become fed up with the housing discrimination, harassment in dormitories, lack of African-American history courses, professors and the unfair grading policies they were being subjected to.

1968 WSU-O student and Advance-Titan reporter Sandra McCreary said she experienced many instances of unfair treatment due to the color of her skin.

“I never knew what a university experience was supposed to feel like,” McCreary said. “The second year, no papers had been filled, nothing had been processed, I didn’t get a room, I didn’t get books, I don’t even think I got a regular set of classes until they were all picked over.”

According to documents obtained by UWO history professor Stephen Kercher, the list of demands included hiring black instructors, implementing courses in the areas of history, literature and language pertaining to black culture and activating a Black Student Fund that would be used to secure black speakers, purchase black literature and aid the financing of the Afro-American Center.

1968 student and member of WSU-O football team Geoff McCreary said he felt like he was never a part of a team.

“I felt very alone,” McCreary said. “I considered the other people on the team more of the opposition than the team we had to play against. I had experiences where … I don’t know if was a cheap shot or what, but he actually cracked a few of my teeth, and I had to go to the dentist.”

The students who appeared in Guiles’ office on Nov. 21 also made a prior effort to submit a list of demands in October. According to Kercher, when no action was taken, the students decided to make “a more forceful and determined list” and hand deliver it.

According to the Black Thursday website created by Kercher and several other UWO members, when the students appeared in the executive offices with the list of demands, “Guiles steadfastly refused, claiming that he did not possess the authority alone to take action. What happened next has been disputed for 40 years.”

One of the ‘Oshkosh 94’ members, Gladys Coleman, whose dreams of attending college ended on Nov. 21, said none of the students who appeared in Dempsey Hall that day could have predicted what would happen.

“I don’t think any of us expected the response we got … ‘You’re criminals, you don’t belong here, get out,’” Coleman said.

According to Guiles and a second administrator present at the scene, a directive to “do your thing” issued by one of the students signaled a, “brief but intense bout of vandalism, with typewriters thrown to the ground, desks overturned, ink spilled onto carpets, windows broken and administrative files and records strewn about.”

McCreary said he wasn’t aware of any plans to overtake Guiles’ office.

“We tried to do it in a respectful way, but he wasn’t respectful to us,” McCreary said.

According to the website, Guiles explained to the black students that he could authorize nothing until he received a report from the committee of faculty and administrators who were coincidentally meeting that same morning to discuss the demands the students had submitted earlier.

The students vowed to sit and wait in the executive offices until the committee issued its report and a timetable for subsequent action was reached with President Guiles. “I can give up a few hours of my life for my future,” one student said as she prepared to wait.

A line of police in riot gear appeared, following Oshkosh Police Capt. Robert Kliforth’s order to vacate the offices. The students were escorted outside of Dempsey Hall by helmeted police and were then herded into rented Hertz trucks waiting outside to take the students to the Winnebago County Courthouse.

According to the website, the students were formally charged with unlawful assembly and disorderly conduct, arraigned and then distributed to prisons as far away as Green Bay.

According to Kercher, two central questions concerning the treatment of the black student demonstrators emerged in the early phases of their civil trial and the campus disciplinary hearings: Would the students be prosecuted as a group or as individuals, and, in the face of bitter public enmity, how would students’ procedural rights be protected?

Milwaukee civil rights attorney Lloyd Barbee, representing a great majority of those arrested, insisted that the black student defendants — all of whom faced the possibility of two-year prison terms — receive individual trials.

A similar plea to the WSU administration and Board of Regents was rejected, thus triggering a long and complicated legal battle that ended up in the U.S. District courtroom of Judge James E. Doyle. On Dec. 6, Doyle ruled that WSU-O had to hold a hearing by Dec. 20 in order to determine the students’ futures at the University.

During the hearing, only one of the Oshkosh 94, Willie Sinclair was able to testify about his involvement in the demonstration. According to the website, “in the end, neither the testimony of Sinclair, the protestations of the students’ attorneys, the presentation of facts nor the sanctity of due process itself were any match for the Board of Regents’ determination to punish the Oshkosh 94.”

Sandra McCreary said she felt the trial was unfair.

“They didn’t research or ask for input from any of the students; they were just there to condemn us,” she said.

On Dec. 20, Regent W. Roy Kopp of Platteville delivered the board’s unanimous decision to expel 90 of the Oshkosh 94. Four other students were only suspended since their attorneys were able to prove that they were not in Dempsey Hall when the damage occurred on the morning of Nov. 21.

1968 social studies professor Claud Thompson said some members of the ‘Oshkosh 94’ were in a class he taught.

“Two of the takeover participants were in my social studies methods class, and I was very sorry that they were expelled, since they were probably roped into the action,” Thompson said.

One of several white students, John Schuh, charged with the task of notifying the parents of ‘Oshkosh 94’ students of their imprisonment on Nov. 20 said the actions taken were unnecessary.

“In my view, institutions can either manage the events and respond appropriately or as the old cliché goes, bring gasoline to the fire, and I think in the case of what happened in 1968,” Schuh said. “I’m afraid the senior leadership brought gasoline to the fire.”

In February 1969, due to the large amount of student protest demonstrations, members of the student government voted in favor of a strike, which would force the University to shut down.

According to Kercher, Guiles managed to prevent a strike by promising the WSU-O students a special investigation into the Black Thursday demonstration. Allegations that professors in the departments of history, English, political science and international studies who sympathized with the Oshkosh 94 were being fired or intimidated by the WSU administration.

Members of the UW Madison Black People’s Alliance approached their campus administration with a list of demands asking “that the University use all influence with the Oshkosh administration to re-admit those students … and failing this [see to it] that they be admitted to the University of Wisconsin next semester without prejudice.”

Ten months after Black Thursday, WSU-O committed itself to making a series of improvements for black students on campus. According to the website, it recognized a new black student organization, the Afro-American Society, and converted the campus Intercultural Center into a new Afro-American Center. Under the direction of new black assistant dean of students, Curtis Holt, the Afro-American Society and Center began sponsoring a speakers series, music festival and a black theater workshop. Faculty members such as Virginia Crane began offering classes on black history and literature.

Many of the ‘Oshkosh 94’ still continued to face hardships after Black Thursday. A 1968 music student at WSU-O, Henry Brown, was one of them.

“UWM had accepted me for the January semester, and I had attended classes for about a week and then they came back and said, ‘Wait a minute, this guy went to Oshkosh, we can’t have him on our campus.’ Then they revoked my admission after I was going to school and everything,” Brown said.

Thompson said he was aware of obvious tension between students after the Black Thursday events took place.

“My perception is that most white students were hostile to those students who took over the chancellor’s office,” Thompson said.

Editor’s Note: Many of the facts and interviews presented in this article are contributions from Dr. Kercher and the Black Thursday website, which can be found at http://www.blackthursday.uwosh.edu/blackthurs.html.