UW Oshkosh is making progress toward its 2030 sustainability goals, Sustainability Director Brad Spanbauer said, with many energy conservation and education projects at UW Oshkosh and across the Universities of Wisconsin System in various stages of implementation.

“We’re trying to make our buildings just generally more efficient, trying to establish renewable on-site renewable energy sources,” he said.

Chancellor Andrew Leavitt signed a climate leadership statement in April 2022 and outlined the university’s goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2030.

Two years prior, two former students helped garner nearly 600 signatures for a petition calling for UWO to reach carbon neutrality by the end of the decade.

UWO had already been implementing sustainable energy sources going into the 2020s, in part by installing solar panels atop of buildings and by constructing the country’s first commercial-scale dry fermentation anaerobic biodigester as a power source.

The university’s 2030 sustainability goals also include turning the Sustainability Institute for Regional Transformations (SIRT) into a leader in sustainability research, education and practice, as well as a collaborator within the community.

Reaching carbon neutrality

SIRT’s website outlines the university’s carbon neutrality goals in more detail, outlining goals for scope one, two and three emissions — categories established by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol to help organizations better measure and manage their greenhouse gas emissions.

Scope one emissions refer to those directly owned by a company or organization, such as UWO. Scope two refers to purchased emissions, such as buying electricity from a power plant. Scope three emissions are those used but not owned or directly controlled by a company, such as the emissions produced when flying on a plane.

According to SIRT’s website, UWO aims at becoming climate neutral for scope one and two emissions by 2030 via replacing aging fossil-fuel combustion infrastructure with electric alternatives and by pursuing renewable energy alternatives.

The plan stated a goal of reaching carbon neutrality for scope three emissions by 2035 through “implementing a comprehensive program that allows for offsets associated with business operations, athletics and study abroad travel.”

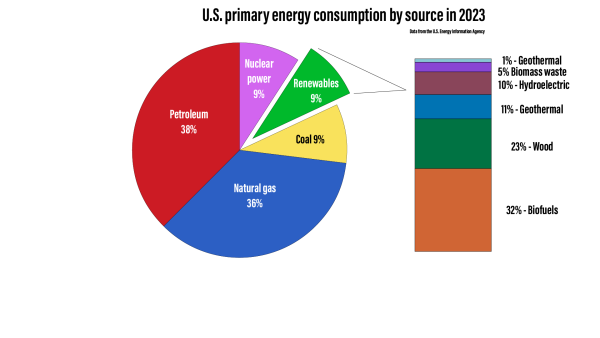

Spanbauer said switching from coal to natural gas in the university’s heating plant in 2020 was a big step forward in reaching carbon neutrality. The emissions from coal are about double that of natural gas.

“That put us on a trajectory for the emissions from our heating plant to slowly get away from carbon-intensive sources,” he said. “Natural gas is definitely still a fossil fuel. It’s not something we want to use long-term, but it is cleaner than coal … [coal] puts a lot of particulate material into the air, lots of mercury and other stuff which is really, really dangerous.”

He said that UWO still uses low-sulfur fuel oil as a backup, though mostly in the winter when the temperatures are much lower.

“That’s because we’re a large customer within the Wisconsin Public Service sector,” he said. “When you’re a large customer, they can put you on curtailment. … When it gets cold enough, they can shut off your supply of natural gas to ensure that residential home owners have enough natural gas supply to come through the pipeline system to feed their homes.”

Tasked by Leavitt last June to save the university $1 million, Spanbauer said he wanted to take proactive, fine-tuning measures to improve energy conservation across the campus. This includes turning off lights and reducing the runtime on the university’s HVAC equipment, which is responsible for heating, cooling and ventilation.

“We were able to make a huge leap and make a lot of ground very, very early in the fiscal year,” he said. “It’s a lot of simple stuff like turning off lights, unplugging, changing some of these occupancy sensors.”

The light occupancy sensors in buildings, he said, were set to their highest sensitivity setting, meaning they could be triggered extremely easily, and they’d stay on for 15 minutes once triggered. The sensitivity was reduced, and they now only stay on for three minutes.

“We saw numbers drop pretty rapidly,” he said. “In November and December between 2022 and 2023, in [Sage Hall], we shaved off over 20,000 kilowatt hours each month.”

The average U.S. household uses about 10,000kWh of energy every year according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

One of UWO’s longer-term sustainability plans involves renovating Polk Library. The Board of Regents approved $137.5 million for the renovation of the Polk Library in August 2024.

The renovation will further UWO’s 2030 sustainability goals, Spanbauer said, in part by sporting solar panels that may produce enough energy to backfeed into other buildings and by having a self-contained geothermal system.

Polk Library Director Sarah Neises said that the new proposed library will be almost 40,000 square feet smaller and that other aspects of the new library will change to make it more efficient all around.

“Print collections now consume 55% of the square footage. In the new building; they would take up 30% of the square footage [in the new library],” she said. “Reduced collections will be more efficient and sustainable. In the new building, the print collection is not projected to grow but stay the same through consistent deselection processes. Some materials will be shelved in the basement in compact shelving to reduce the footprint of collections in the main study areas.”

She also said that if Polk is open, the entire building must remain open and be heated and cooled. However, the new library may sport a 24-hour card-access study zone, allowing the library to reduce lighting, heating and cooling to other areas. The new library will also use other lighting methods.

“Methods of ‘daylighting’ through skylights will bring daylight into study areas, making them more appealing for students at different times of the day,” she said.

She also said that the designers are hoping to re-use the Valders limestone currently on the outside walls of Polk, reducing the amount of new materials that would have to be sourced.

On a broader scale, Spanbauer said another thing being pushed at the state level is a virtual power purchase agreement.

“The schools within the UW System would all band together, and we would invest in a large-scale renewable energy operation,” he said. “Think of building a wind farm or a solar farm, ideally in the state of Wisconsin.”

The UW System would essentially buy into the total amount of energy produced by the system, allowing them to take out the energy they need to power the system’s schools.

According to emails sent to and from Spanbauer obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, the university has been retrofitting LED lights as the current fluorescent lights have burnt out. The emails discussed the cost of replacing the lights and the possibility of outsourcing their systematic replacement but did not establish anything concrete.

In one of the obtained emails from February 12, Spanbauer said that the Universities of Wisconsin System is working toward a more permanent and unifying energy data management experience through a dashboard system.

“Once this project is completed, all of the universities will have access to building level data that will also integrate their billing information and will allow us to be able to map trends, outliers and overall be better able to understand our utility consumption and spend[ing],” he said in the email. “I anticipate that full roll out and implementation will likely take through next academic year.”

Sustainability through SIRT

SIRT Director Stephanie Spehar said SIRT is moving toward its 2030 goals by increasing its research activity and capacity and by supporting the work and teaching that occurs on campus. Prior to university budget cuts amid its $18 million deficit, SIRT was providing grants to faculty and staff for interdisciplinary sustainability initiatives ranging from curriculum development to public art and climate research.

One of these initiatives funded the development of a sustainability-focused art course in the art department, while another addressed climate change through installing public art projects about the issue in public spaces at UWO’s access campuses. But she said that SIRT has also addressed sustainability by providing a grant to look at the climate vulnerability and resilience of various counties in the region.

“[It looked at how] resilient are those counties to the effects of climate change and other natural disasters, and especially how [they’re] accounting for the needs of vulnerable populations with things like disaster preparedness,” she said. “For elderly people or people with disabilities or LGBTQ people … how are those sort of more socially-vulnerable populations worked into those plans for disaster preparedness?”

She said that SIRT recently received a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study harmful algal blooms in Lake Winnebago and the adjacent waterways, a project that’s so far employed more than 30 UWO students.

“[This project brings together] seven or eight different faculty and staff at UWO from all sorts of different disciplines, ranging from anthropology to chemistry to biology to environmental studies to geography,” she said.

Bringing in external funding, such as funding for the algal bloom project or for the various agriculture projects SIRT assists in, is a key area of development for SIRT, she said.

“I think it’s really helped establish us as a legitimate place where interdisciplinary sustainability research is happening,” she said. “Part of the reason we’re involved in the sustainable agriculture projects is because we got that NSF funding for the harmful algal blooms work, and so we are now, through research, a place where innovative research on sustainability is happening, and we can legitimately say that.”

Spehar said that while the type of research SIRT does allows for a better understanding of the environment and people’s beliefs about it, SIRT can also help UWO’s sustainability efforts through developing curriculum and community engagement.

“Being a sustainable institution isn’t just about having, you know, good light fixtures,” she said. “It’s about having sustainability be an integral part of the education we’re doing.”

She said SIRT is helping accomplish this by providing more opportunities for students to engage in real and active sustainability research and opportunities. But, as the university is shifting its academic structure and offerings, Spehar is trying to develop a sustainability attribute for classes.

“[This would basically be] something that designates courses as being sustainability focused,” she said. “And the idea is that all students would have to take one of those classes before they graduate from UWO. So regardless of their major … they have to take a sustainability-related course. And the idea is we’ll make sure these are available across the university, across disciplines. So this won’t be hard for students to do.”

She said that SIRT also benefits the university’s sustainability efforts through events that hope to engage everybody with sustainability. These include bringing in speakers, doing panels and hands-on events like trash pickups and tree plantings.

“Our institution can’t be sustainable if our broader community isn’t,” she said. “We can’t be a little fortress of sustainability. … Our job as an institution of higher education is to be a model for our community and to really reach out to our community and provide.”