UW Oshkosh faculty, staff and members of the Oshkosh 94 — a group of African American students who were expelled after protesting for equal rights on campus — spoke during a remembrance ceremony about the protest and its lasting impacts.

The event, which featured a panel of former students who were expelled following the 1968 protest, aimed to highlight the history of racial discrimination on campus and in Oshkosh, and how the community and campus have changed since.

In addition to the Oshkosh 94 members who spoke, UWO Professor of History Stephen Kercher and university archivist Joshua Ranger also gave presentations during the event.

The history of Black Thursday

UWO, named the Wisconsin State University-Oshkosh (WSU-O) at the time, was growing rapidly. WSU-O was the largest public university in northeast Wisconsin in the 1960s, and by the end of the decade, it was one of the fastest growing universities in the country.

With increasing enrollment came flocks of new students, many of whom were African American. Kercher said that Oshkosh, like many of the surrounding cities, had a very small minority population.

“There used to be a larger African American community in Oshkosh [prior to the 1950s and 60s],” he said. “[But] these populations were either driven out or intimidated to make them feel unwelcomed.”

So the growing African American population at WSU-O was often met with mistreatment and ostracization.

One of the event attendees explained his experience on campus during this time while playing on the basketball team.

“I played with athletes that didn’t want to be involved with me [and] didn’t want me on the team,” he said.

When riding to away games, he said he had to sit in the back of the bus by himself.

“I would sit in the back of the bus and put my sunglasses on so they couldn’t see the hurt in my eyes,” he said. “And the coach would come back to me and say, ‘How are you? Are you going to be alright?’ I said, ‘I’ll be ok.’ But I was hurt.”

Continued mistreatment and discrimination led to the organization of Wisconsin’s first Black Student Union (BSU) in February 1968. The BSU advocated against the mistreatment of African American students in dormitories and in favor of fair grading policies, as well as African American history and literature courses.

But their requests went unanswered and, as the African American population on campus grew in fall 1968, racial tensions escalated.

Kercher stated on his website dedicated to Black Thursday that students were regularly called racial epithets, taunted and that, in at least one recorded instance, pelted with rocks by local teenagers.

Continued mistreatment by students, locals and the WSU-O administration led members of the BSU in October 1968 to give the administration a list of requests, including African American history and literature courses, the hiring of black faculty and the creation of an African American Cultural Center.

But by November, as time passed and nothing had appeared to be done, members of the BSU became impatient. Determined to make their voices heard, they agreed to march to the executive offices in Dempsey Hall the following day and confront university President Roger Guiles.

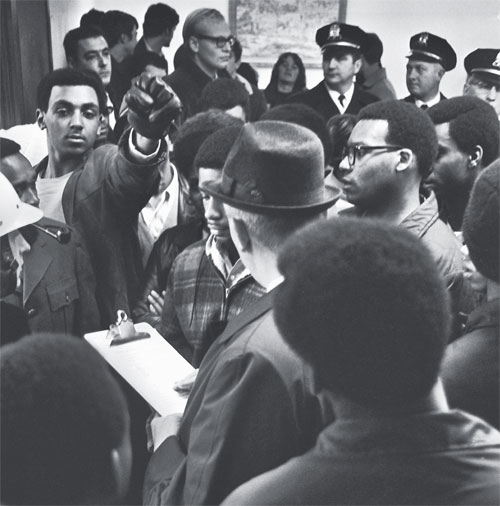

On the morning of November 21, 1968, 90 African American students organized with a list of demands for Guiles to sign.

Entering Guiles’ office, a group of the students presented him the list, which he rejected, saying that he did not have the sole authority to enact the demands.

Accounts of what happened after Guiles denied the demands varies, but, Kercher stated on his website, a spout of vandalism ensued, with “typewriters thrown to the ground, desks overturned, ink spilled onto carpets, windows broken and administrative files and records strewn about.”

Resolved to see change, students vowed to wait in the executive office until the appropriate actions were taken to enact the changes.

In the midst of the commotion, a group of white students and plainclothes police officers had amassed outside of Guiles’ office. Shortly after that, a group of Oshkosh police officers in riot gear showed up.

The students were arrested and received charges such as unlawful assembly and disorderly conduct, with some being taken to prisons as far away as Green Bay.

News of the incident spread, causing black rights activist James Groppi to travel to Oshkosh in a show of sympathy. Additionally, nearly 1,000 activists marched down Algoma Boulevard toward the Winnebago County Courthouse in a show of support.

Continued protests caused Guiles to close WSU-O five days before Thanksgiving break in an effort to lower tensions. Guiles also sought to permanently expel the students who entered his office.

Some students were given the choice of returning to WSU-O, but most pursued their education at other universities.

Oshkosh 94 member Richard Brown said that, after he graduated from high school in 1968, he received a letter stating that, if he agreed to become a teacher, he would be financed for free. So he came to WSU-O.

“I was only here for about three months, and after I was expelled from all the universities in Wisconsin, I went to the University of Missouri, Lincoln University, ACB College,” he said. “And I fulfilled my ambitions and became a teacher, and I taught for 28 years at Rufus King,” he said.

Kercher’s website on the history of Black Thursday can be found at blackthursday.uwosh.edu/index.html.

Black Thursday’s impact

During a Q&A session, the panel of Oshkosh 94 members discussed what has changed since Black Thursday. Sheila Knox said that she’s seen a lot of changes on campus since then, including a lot more diversity.

“Many of the African American faculty and staff that you see were not there then [in 1968],” she said. “There is a women’s center and a black studies program. There are many things you may take for granted that are here.”

Joel Johnson also said he’s seen a lot of change since then.

“The African American multicultural center still exists; it started in 1969,” he said. “And I’m proud to see that it’s still housed on campus.”

Robert Hayes said that there were about seven African American students on campus when he arrived in 1965. And, despite the positive change that’s developed since then, there have been some negative changes, too.

“I never thought, 60 years ago, that we would be taking some steps backward,” he said. “When you’re talking about critical race theory, taking books and things out of the libraries. … That’s a change also, but it’s not a change for the better. You can’t learn one way and about just one culture. Those are things students have to stand up for.”

The panel also thanked UWO Chancellor Andrew Leavitt for his apology to the Oshkosh 94 and their families during a Black Thursday remembrance event in 2018. Leavitt is the first university administrator to formally do so.

Another change highlighted by the panel was the creation of the Center for Student Success and Belonging, which aims to help students reach their full potential at UWO through various initiatives. Byron Adams, the center’s director, spoke about how the Oshkosh 94 impacted the center’s creation.

“I think the reason we have so many support services on campus … is because of the efforts of the Oshkosh 94,” he said. “I’ve been on campus now for 20 years … so I’ve seen a lot of the changes that have happened.”

He also encouraged students to stay engaged and advocate for the things they need.

“Engagement works,” he said. “Using your voice, making sure that your needs are being met, and challenging us — as staff, administration, as faculty — to make sure that your needs are being met and you’re getting the experience you’re paying for, is important. You see the fruit of what that kind of action does.”